March 20 2005

Good afternoon.

Thank you for attending, and thank you Kathleen Thorne for inviting me

to come to this lovely island to speak.

The topic you gave me was “a discussion of how Shakespeare might view

today's rulers, the role of war, and other current topics, and what we can

learn from his writings that is still relevant to today's issues and

events.”

To begin with, I’d like to consider what prompts this

topic. We are interested in it

because Shakespeare is an author with Clout—his works comprise a treasury of

cultural capital.

Cultural Capital is a term invented by the French

sociologist Pierre Bourdieu that has gained currency among scholars in a

variety of fields, especially those associated with the school of New

Historicism that emerged in the early 1980s. New Historicists concern themselves with the interplay

between art, money and power, and they study works of literature in social and

historical context. They ask how

works of art embody, support and challenge the ideology of the power structure of the times and places

they were produced, and also how they function as tools of power and ideology

in later times. Most of my talk will focus on these questions—how is

Shakespeare’s clout used by people in and out of power today, and how did

Shakespeare relate to some of the political issues of his own time. It’s no accident that New Historicism

originated among Shakespeare critics like Stephen Greenblatt, since Shakespeare

has accumlated more prestige or cultural capital than any other writer or text

since his time.

The recent film release of the The Merchant of Venice, now playing on Bainbridge Island, brings to mind some of Shakespeare’s own reflections on the use of revered texts for local political and economic purposes, specifically the one text with even more clout than his own: the Bible. A central theme of this play--the rivalry between Christians and Jews over interpretation of the Holy Scriptures—is dramatized in the spectacle of Old and New Testament references being flung back and forth by the rivals like brickbats . But the underlying theme of conflicting appropriation of authoritative texts emerges in this kind of language:

The

devil can cite Scripture for his purpose. . . . O what a goodly outside

falsehood hath!' (1.3.96-7, 101)

or

'In religion, | What damned error but some sober brow | Will bless it

and approve it with a text | Hiding the grossness with fair ornament?'

(3.2.77-80).

As with the Bible, so with the Bard: liberals and conservatives, Democrats and Republicans, neocons and libertarians, generals and war protesters all claim to have them on their side.

Here’s an example of Shakespeare’s from the days of my

youth

http://www.brumm.com/MacBird/index.html

More recent examples abound on the other

side of the political spectrum.

http://www.moversandshakespeares.com/index.html

This is a very successful enterprise catering to CEO’s,

Politicians, and Military Top Brass. It’s run by Carol and Kenneth Adelman, a

Republican political consultant who was President Ronald Reagan's chief adviser

on arms control. A member of Rumsfeld’s Defense Policy board, he is famous for

the remark that the war in Iraq would be a cakewalk. One of their clients is James G. Roche, former secretary of

the Air Force, for whom the couple had run seminars between 1999 and 2001 while

he was a vice president at Northrop Grumman. For the last two years they have

been contracted to do this for the military at taxpayer expense.

The most popular of Shakespeare’s

plays among the movers and shakers is Henry V. According to an article by

Scott Newstok, it “enjoys an

unchallenged predominance on syllabi for graduate courses in leadership and

public policy -- for instance, excerpts from this play (and this play only)

appear in at least five courses at The Kennedy School of Government

alone. .. An Army major general

recited the Crispin's day speech to his troops before deployment in this second

Gulf buildup;

and publishers donated copies of Henry V to U.S. military personnel as part

of a revived 'Armed Services

Edition'."

The myth of Henry V has a long ancestry. Ruling between 1413 and 1422, Henry has always been England’s hero king, celebrated before Shakespeare in Tudor chronicles and an anonymous play called “The Famous Victories of King Henry the Fifth.” Known affectionately as Hal or Harry, Henry defeated rebellion at home and achieved conquest abroad. As a prince he started out as a barfly, robber and prodigal son, but upon inheriting the throne, he miraculously converted to a serious general, conqueror of France and victor of the Battle of Agincourt. He galvanized the divided nobility, common folk and clergy into a unified force of enthusiastic followers and died young, in the words of Shakespeare’s chorus, “a star of England.”

Shakespeare’ biographical history of this King combines

action, suspense, romance, and stirring patriotic rhetoric with deep

characterization emphasizing the difference between the king as charismatic

performer on the stage of history and his internal struggle with fear,

resentment and doubt. Shakespeare also gives voice in the play to trenchant

criticism of the King and his policies.

At its core, his Henry V is a study of successful political leadership,

the embodiment of Machiavelli’s Prince.

From early on, both the historical Henry and Shakespeare’s version have elicited strongly opposed responses.

Throughout the nineteenth century productions of the play

were staged to glorify the expansion of the British Empire with emphasis on the

cry in Act III, “God for Harry, St George and England.” The propagandistic

nature of the play reached its pinnacle with Sir Laurence Olivier's film,

promoted and financed by Winston Churchill. Premiering in 1944,

its aim was to raise English spirits during the dark days of World War II. All these productions were heavily cut,

deleting the many passages of the

text that might question the idealization of the hero.

The contrary view has a long lineage as well. In the early nineteenth century, the Whig essayist William Hazlitt had this to say:

“HENRY V is a very favourite monarch with the English nation, and he

appears to have been also a favourite with Shakespear, who labours hard to

apologise for the actions of the king, by shewing us the character of the man,

as "the king of good fellows." . . . Henry, because he did not know

how to govern his own kingdom, determined to make war upon his neighbours.

Because his own title to the crown was doubtful, he laid claim to that of

France. Because he did not know how to exercise the enormous power, which had

just dropped into his hands, to any one good purpose, he immediately undertook

(a cheap and obvious resource of sovereignty) to do all the mischief he could.”

During the Vietnam era, productions by The Royal

Shakespeare Company in Stratford, the Canadian Shakespeare Festival and the

American Shakespeare theatre took strongly anti-Henry anti war stances.

Kenneth Branagh’s 1989 theatrical production and popular

film, reflecting an influence of the recent Falklands war and partially

financed by Prince Charles. took a somewhat balanced view of the war,

displaying its grittiness and brutality, but in the end thoroughly glorifying

the young king—as well as its young director and star.

In recent years it has become commonplace

to read comparisons between Henry and

George W. Bush

Conservative commentators after 9/11 and before invasion of

Iraq used them to glorify the new president

* "I thought that last Friday, as Bush stood atop part of the

rubble of the World Trade Center, he came as close as he ever will to

delivering a St. Crispin's Day speech. That spirit and resolve carried over

into the House chamber last night, and it was something to behold." -- Rich Lowry

* "In Bush, the country discovered it had a young leader rising to

the occasion, an easy-going Prince Hal transformed by instinct and circumstance

into a warrior King Henry." -- Chris Matthews

". . . when trouble hit, how rapidly we left behind the pages of

Henry the 4th and suddenly we seem to be into the pages of Henry the 5th. There

had been a transformation as young George W. Bush stepped up to bat. Now, to be

sure, he has not won his Agincourt, but he has set sail, and for that the

country can be grateful." David Gergen

Liberal commentators have taken just as much relish either pointing out the fallacies of the comparison or showing how the president manifested some of Henry’s less than inspiring scharacteristics:

1. The fact that he follows the famous advice offered him

by his father upon his deathbed

Therefore, my Harry,

Be it thy course to busy giddy minds

With foreign quarrels; that action, hence borne out,

May waste the memory of the former days.

2. The fact that Henry repeatedly shifts

to others his responsibility

for civilian deaths;

3. The fact that the clergy support is gained by Henry as

quid pro quo for his opposition to a bill in parliament that would expropriate

their lands.

One possible application of Shakespeare’s Clout to

contemporary events was suggested in a speech by Mackubin Thomas Owens, a

professor of strategy and force planning at the Naval War College. He urged

that a speech of Henry's "be printed in Arabic on leaflets and dropped on

Baghdad, Basra, and especially Tikrit….King Harry’s speech before the gates of

Harfleur might make those Iraqis who claim they are willing to die for Saddam

think twice.”

http://www.ashbrook.org/publicat/oped/owens/02/shakespeare.html

This is the latest parle we will admit:

Therefore to our best mercy give yourselves;

Or like to men proud of destruction

Defy us to our worst: for as I am a soldier,

A name that in my thoughts becomes me best,

If I begin the battery once again,

I will not leave the half-achieved Harfleur

Till in her ashes she lie buried.

The gates of mercy shall be all shut up.

.....

What is it then to me, if impious war,

Array’d in flames like to the prince of fiends,

Do, with his smirch’d complexion, all fell feats

Enlink’d to waste and desolation?

....

What say you? will you yield and this avoid,

And as typical with such appropriations of cultural

capital, the text is quoted out of context. Here are the lines in that speech which are effaced by Owens’

ellipses

And the flesh'd soldier, rough and hard of heart,

In liberty of bloody hand shall range

With conscience wide as hell, mowing like grass

Your fresh-fair virgins and your flowering infants.

…What is't to me, when you yourselves are cause,

If your pure maidens fall into the hand

The blind and bloody soldier with foul hand

Defile the locks of your shrill-shrieking daughters;

Your fathers taken by the silver beards,

And their most reverend heads dash'd to the walls,

Your naked infants spitted upon pikes,

Whiles the mad mothers with their howls confused

Do break the clouds, as did the wives of Jewry

At Herod's bloody-hunting slaughtermen.

Though this passage makes Henry appear quite monstrous, the full text of the play adds more

complexity by suggesting this is really a brilliant bluff that intimidates the

fortified town into surrender without bloodshed, though Henry and his exhausted

troops were incapable of carrying out the threat.

The debate over Shakespeare’s Henry was

itself turned into a grand performance at the Shakespeare theatre in Washington

D.C. in May 2004

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A34918-2004May17.html

"Let's see what we have here. We have a king whose father had been

a king. We have a king who spent a carousing youth," said industrialist

and Shakespeare Theatre trustee Sidney Harman as he introduced the program.

David Brooks talked about the fact that while prewar counsels could emphasize prudence, it was a wartime leader's job to rally a martial spirit and "get people to stop thinking prudently."

Ariana Huffington…vigorously demurred, spitting out a stream of

comparisons unflattering to both Henry V and George II. Henry's invasion of

France was not an invasion of necessity, she said, but one of choice -- and

"there can be no moral war of choice."

Ken Adelman, [he keeps showing up] talked about Henry's much-debated

decision at Agincourt.. to order his French prisoners killed.

Adelman… last week had explained to a reporter that he was

"ducking" press calls about Abu Ghraib.

At the end of the Shakespeare Theatre debate, Isaacson turned the job

of judging a "winner" over to Dame Judi Dench, the great British

actress … Dench professed herself unfit for the task: She's a Quaker, she said,

and cannot understand why such wars should begin. Then she turned to the last

lines of "Henry V," spoken by the chorus, as a way of summing up.

"This star of England: Fortune made his sword," she read,

"by which the world's best garden he achieved." Yet it was all for

naught, because the young Henry VI and his advisers promptly "lost France

and made his England bleed."

Appropriating Shakespeare’s Clout to

declare what he would think about present day political issues is risky

business, since we have no record of his opinions, only those he put into the

mouths of his characters. And they

contradict one another and themselves, and often speak with irony or sarcasm.

Nevertheless it’s tempting to look for what the dramatist himself might have

been thinking about politics in the context of events and debates of his own time—the sixteenth and

seventeenth centuries, known today as the Renaissance or Early Modern period.

As a teacher of Renaissance Literature I started getting interested in

Shakespeare’s attitudes toward war and peace in 1985, when I worried about what

looked at that time like a heat-up of the cold war between the US and the

Soviet Union under President Reagan.

I was troubled by the fierce militarism of Henry the Fifth since I had first

read it during the Vietnam war. I

was confused by the passages that undermined this stance and also by what

appeared like a fulfledged opposition to war in later plays, especially Troilus and Cressida. Was it

possible to find anything in the culture of this early modern period that could

substantiate and explain Shakespeare’s presentation of what looked like

distinctly modern debates between militarism and its opponents? Four years

later I’d come up with some answers in an essay entitled “Shakespeare’s

Pacifism,” as my own take on “a

discussion of how Shakespeare might view today's rulers, the role of war, and

other current topics, and what we can learn from his writings that is still

relevant to today's issues and events.”

Shakespeare’s Pacifism

Reflection upon war and peace was at the

heart of the Renaissance Humanist

movement, just as the conduct of war and peace was at the foundation of the

European state system during the early modern period.

The humanist response to war and peace

often split into opposing positions categorized as martial vs. irenic--that is

militarist vs. pacifist. Militarists like Caxton, Machiavelli and Guiccardini

lionized an ideal of the prince or courtier as soldier and scholar and regarded

the warrior's activity as essential for individual achievement as well as for

social order.Their pacifist opponents, like Erasmus, Thomas More, Baldassare

Castiglione and Juan Vives envisioned the ideal prince or courtier as a jurist

and philosopher, and criticized the military ethos as irreligious, immoral and

impractical. This debate shaped the actions of monarchs, the deliberations of

councils, the exhortations of divines, as well as the imaginative productions

of artists and writers of the time.

Shakespeare repeatedly dramatized the

disagreement between militarist and pacifist perceptions of warfare in the many

plays he devoted to military matters. In the course of his career, he shifted

from a partisan of war to a partisan of peace . The turning point of this development

occurred between the publication dates of his two battlefield plays, Henry V

and Troilus and Cressida--and that shift in outlook reflects a shift in British

foreign policy that began during the last years of Queen Elizabeth's reign and

was completed with the accession of King James I in 1603

"A prince must not have any other

object nor any other thought, nor must he take anything as his profession but

war, its institutions, and its discipline; because that is the only profession

which befits one who commands." So Machiavelli opens chapter XIV of The

Prince entitled "The Prince's Duty

Concerning Military Matters." His equation of sovereignty with military

strength was both traditional and innovative. Since the fall of the Roman

Empire, European political power and social status were vested largely in a

warrior elite descended from Germanic chiefs. Their martial values and cultural

identity were sublimated by the intellectual and bureaucratic legacy of the

Church of Rome into the institutions of feudalism and the ideology of chivalry,

but Europe throughout the Middle Ages retained the underpinnings of a warrior

culture.

For Renaissance militarists war was an

end in itself, the fundamental condition of social life, individual psychology

and all creation: "There is not in nature a point of stability to be

found; everything either ascends or declines: when wars are ended abroad,

sedition begins at home, and when men are freed from fighting for necessity,

they quarrel through ambition...I put for a general inclination of all mankind,

a perpetual and restless desire after power that ceaseth only with death."

[Sir Walter Ralegh, translating Machiavelli’s Discourses]

But if militaristic approval of war was

dominant, it was by no means monolithic. In 1516, three years after Machiavelli

sent The Prince to his patron, the most prestigious humanist in Europe,

Desiderius Erasmus, published The Education of a Christian Prince (Institutio

Principis Christiani ), which he wrote as a handbook for the future Emperor

Charles V. In it, he advocates an "Art of Peace" contrasted to

Machiavelli's Art of War. Rather than normal health, Erasmus sees war and

violence as aberrant pathology--in nature, in society and in the individual. Rather

than identical with force, Erasmus sees power or authority as distinct from it.

The duty of Erasmus' prince consists not of making or preparing for war, but

rather of avoiding it and serving his people, on whose satisfaction he depends

for legitimacy. Real power and true heroism lie not in physical dominance over

others but in self mastery. To establish and maintain peace should be the goal

of all princes, a goal achieved by the greatest spriritual and temporal leaders

in history, Jesus and Augustus.

In

1517 Erasmus published another of his numerous anti-war works, The Complaint of

Peace (Querela Pacis ), headed with the epigraph, "The Sum of All Religion

is Peace and Unanimity." In it he adds a series of pragmatic objections

against militarism to the spiritual ones in the Instititutio. War is conducted

not for the benefit of the people but for the aggrandizement of princes; the

hoped for benefits of battle--righting wrongs, gaining territory, resolving

disputes, revenging hurts--never approximate the actual costs in lives,

property and social disruption:

"There is scarcely any peace so unjust, but it is preferable, on the whole, to the justest war. Sit down before you draw the sword, weigh every article, omit none, and compute the expence of blood as well as treasure which war requires, and the evils which it of necessity brings with it; and then see at the bottom of the account whether after the greatest success, there is likely to be a balance in your favor."

Between 1517 and 1529 alone, The

Complaint of Peace went through twenty four editions and was translated into

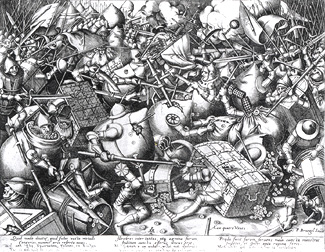

most European languages The visual arts of the sixteenth century display

further evidence of pacifist sentiment. Peter Brueghel's "War of the

Treasure Chests and Money Bags" (1567) illustrates the satirical

indictment of conducting wars for plunder and profit.

The poles of this dispute generate a grid

upon which Shakespeare's plots, characters, and themes can be charted--both in

individual plays and over the course of his career. That career begins with the

Marlovian militarism of the first history tetralogy and the glorification of

violence in Titus Andronicus andTaming of the Shrew, all written during the

early 1590's. In the middle nineties, with King John and the four plays of the

second history tetralogy, the battlefield remains the arena for the exercise of

both individual and collective virtue.

In chivalric celebration of war, in Henry

V Shakespeare aims the full blast of his rhetorical power at the audience . The

choruses inflame us to collaborate with the author in producing a spectacle to

sweep away thought in a flood of patriotic passion. Along with the thrills of

rockets red glare and bombs bursting in air, he invokes the romantic appeal of

battle as an occasion for displaying mettle under fire in the face of bad odds.

Chivalry also provided ethical rationales for war which this play repeatedly

invokes. Since Augustine, the church had evolved a doctrine of "just

war" to regulate the military aristocracy and to exempt it from Biblical

taboos against killing. Justification resided both in legitimate war aims--jus

ad bellum--and in legitimate conduct of fighting--jus in bello. Shakespeare's

Henry is extremely fastidious about securing these justifications, without

which, he avers, his course is one of butchery.

This play also asks us to admire Henry's Machiavellian effectiveness.

It depicts him mobilizing the cynical self-interestedness of all of his

subjects, and it shows his success at melding those conflicting interests into

the common purpose of making war on France.

On the eve of the decisive battle,

Henry declares his Machiavellian

ethos: "There is some soul of goodness in things evil.../Thus may we

gather honey from the weed/And make a moral of the devil himself."

(4.1.1,12) As he kisses Katharine against her will, against custom, Henry

asserts, "nice customs curtsy to great kings...We are the makers of

manners Kate, and the liberty that follows our places stops the mouth of all

find- faults"(5. 2.263). Henry makes his own rules in love as well as in

war, like the hero of The Prince.

On the other hand, as mentioned earlier, many voices in the play undermine this praise and paint the King, in the Welchman Fluellen’s words as “Henry the Pig.”

The debate within the play mirrors the

rivalry in Elizabeths court between the war party and a peace party during the

last few years of her reign—the warriors like Essex and Ralegh eager to lead

protestant England against the Catholic Irish, Spaniards and French, the peace

party of Cecil, Lord Burghley, anxious to avoid foreign adventures and loss of

treasure and life.

Well before her deathbed appointment of

James Stuart King of Scotland as her successor in 1603, Elizabeth knew of his

pacifism. In 1599, James had

published Basilikon Doron, a guidebook for princes dedicated to his own son and

modelled upon Erasmus' The Education of a Christian Prince. Like the 1611

edition of his Works, the frontispiece of this book prominently featured a

picture of "Pax" carrying an olive branch and treading on a figure of

vanity staring in the mirror. Whether or not that figure represents Essex, his

brand of swashbuckling militarism went out of favor during the final Tudor

years. The dominant Stuart mode of expression might be characterized as a culture

of pacifism.

Troilus and Cressida, written in 1602 or

1603, marks a turning point. In it Shakespeare mounts an attack on classical

war heros and on the very arguments for going to war he had supported earlier,

and he undermines the whole set of values and symbols that constitute

Renaissance military culture. The plays of Shakespeare's "tragic

period" which follows Troilus and Cressida continue to focus on the

problem of war, but with a deepening psychological penetration. Othello,

Macbeth, Anthony, Timon and Coriolanus all are great generals whose martial

virtues are shown to be tragically flawed. The plays in which they are

protagonists reveal that military power, the highest value of both the hero and

his society, is a concomitant of deficiency in power over oneself and finally

the loser in a battle with the greater power of love.

Troilus forms a companion piece to Henry

V. Instead of glorifying, it condemns war and those who make it. In the earlier

play Shakespeare counters pacifist objections to war with militarist

rationales; here, he counters militarist rationales with pacifist objections.

In reducing war from a providential tool to an instrument of chaos, he inverts

the rhetorical strategies of Henry V and also shrinks the proportions of epic

to the distortions of satire. The chorus of Henry V apologizes for

"confining mighty men" of his story in the "little room" of

the theatre, implying that the members of the audience are midgets in

comparison to the heros who will be portrayed on stage. The prologue of

Troilus, on the other hand--"armed, but not in confidence"--

introduces us to "Princes orgulous" with "chafed blood" and

"ticklish skittish spirits," whom we may "like or find fault as

our pleasures are." Compared to the self-inflated Lilliputians on stage,

we spectators are cast as gods.

The two major sources of the plot, Chaucer's Troilus and

Creseyde and Chapman's translation of the Iliad, suggest the two militaristic

ideologies which the play continually invokes and mocks: medieval Christian chivalry

and classical pagan policy. These are usually associated respectively with the

Trojans and the Greeks. The question of jus ad bellum --what is the just cause

for making war?--is deliberated by the Trojan council just as it is by the

king's council in Henry V. When

Hector warns against the double evil of violating the laws of marriage and the

laws of nations, Troilus rejects reason itself in favor of "manhood and

honor": "Manhood and honor/ Should have hare hearts, would they but

fat their thoughts/ with this crammed reason. Reason and respect/ Make livers

pale and lustihood deject"(2.2.45-8). Emphasizing the very absence of jus

ad bellum and the consequent immorality and irrationality of making war, Hector

ignores his own reasoning, abruptly reverses his position, and goes off with

Troilus to celebrate their coming victory.

The justice of the Greeks' war aims in

reclaiming Helen is never mentioned; their militaristic rationales are not

chivalric. But their two Machiavellian mechanisms of policy, force and fraud,

are set at odds in the struggle between Achilles and Ulysses, the lion and the

fox. Thus split, the Greeks are as incapable of achieving their own purely

pragmatic purposes for war--morale, prestige, and conquest--as the Trojans are

incapable of achieving honor and love.

As Thersites the clown: "the policy of these crafty-swearing

rascals...is proved not worth a blackberry, whereupon the Grecians begin to

proclaim barbarism and policy grows into an ill opinion" (5.4.10).

It is the fool's perspective--the

perspective of an outsider critical of assumptions that in general are taken

for granted--that marks Troilus and Cressida 's genre of satire. A year after

the play's first appearance, another anti-militarist satire called Don Quixote

was published in the nation that most Englishmen thought of as their

"natural enemy." That same year King James made a lasting peace

treaty with Spain.

If war is no longer validated either by a

heroic tradition or by the arguments of Realpolitik, one is forced to confront

the question of why human beings continue to wage it and suffer its attendant

disasters. By seeking the answer to this question with the analytical and

educational approach to social action of the old Christian Humanists,

Shakespeare and other writers under James Stuart’s rule undertook pyschological

and political studies of warriors and war-oriented societies in the attempt to

understand and reform them. Many of their plays depict the demise of great

military heros, not through the triumph of superior arms, but through failures

of insight, compassion, and self-control attributable to an identity forged in

battle.

Othello, for example, though possessing the martial virtues of

"the plain soldier," is shown to lack the learning necessary to exert

self- mastery and leadership in civil society. His deprecatory self-

description turns out ironically accurate when it comes to his inability to

communicate with anyone but Iago: "Rude am I in my speech,/And little

bless'd with the soft phrase of peace...And little of the great world can I

speak/More than pertains to feats of broils and battles" (1.3.81).

Othello's confidence too is based on war, but the base is shaky and the support

is portrayed as dependency. His prowess leaves him defenseless against those

who prey upon him and dangerous to those he should protect. Even his very

identity as a soldier is shattered by his underlying personal, sexual, and

social insecurity:

O now forever

Farewell the tranquil mind! farewell content!

Farewell the plumed troops and the big wars

That make ambition virtue. O Farewell!

Farewell the neighing steed and the shrill trump,

The spirit-stirring drum, th' ear piercing fife

the royal banner, and all quality,

Pride, pomp, and circumstance of glorious war!

Farewell! Othello's occupations's gone. (3.3.347)

Of all the plays, Coriolanus carries

forward this effort in the most concerted manner. The play criticizes war by

repeatedly showing how military violence takes on a life of its own, severed

from its purposes and justifications. The heroic Coriolanus switches from the

defender of his city to its attacker because of a personal grievance:

"O world thy slippery turns! Friends

now fast sworn...on a dissention of a doit, break out/ To bitterest enmity: so

fellest foes/...by some chance/Some trick not worth an egg, shall grow dear

friends/and interjoin their issues" (4.4.12). And his erstwhile opponents,

" patient fools/Whose children he hath slain," ignore their enmity

and " their base throats tear/With giving him glory" (5.6. 50).

Following Erasmus' path, Shakespeare

traces the causes of political violence to psychological aggression. Even

before Coriolanus' first appearance, a citizen suggests the connection between

the general's battlefield heroics and domestic neurosis: "Though

soft-conscience'd men can be content to say it was for his country, he did it

partly to please his mother and to be proud..." (1.1.37). As the play proceeds, the more he seeks

to confirm his manhood in battle, the more infantilized he becomes.

Like Macbeth's, Coriolanus' compulsive need to fight results

largely from his vulnerability to the influence of a woman's vicarious

aggression. His mother, Volumnia, is introduced as a horrifying creature:

"if my son were my husband, I should freelier rejoice in that absence

wherein he won honour than in the embracements of his bed where he would show

most love...had I a dozen sons...I had rather had eleven die nobly for their

country than one voluptuously surfeit out of action...the breasts of Hecuba/

when she did suckle Hector, looked not lovelier/than Hector's forehead when it

spit forth blood/at Grecian sword, contemning"(1.3.20-80).

In addition to mocking, criticizing and

analysing militarism, Coriolanus demonstrates the possibilityof stemming the

tides of war and civil strife set in motion by its excesses. Its depiction of

Rome's transformation from a warlike to a more pacific society recapitulates

the evolution of England's foreign policy as well as of Shakespeare's political

position between the early 1590's and 1608. The structure of the play's plot

and its manipulation of dramatic tension induce the audience to move in a

parallel direction. When they want to have him elected to political office,

both his friends and his mother regret having intensified Coriolanus' hatred of

the commons and the Volsicans. In the third act they belatedly try to teach him

the peacetime virtues of tact and compromise:

"You are too absolute ...I have heard you say /

honor and policy like unsevered friends/ I th' war do grow together: grant that

and tell me/ In peace what each of them by th' other lose/ That they combine

not there. Throng our large temples with the shows of peace/And not our streets

with war "(3.3.36).

After having created such a Frankenstein

monster, mother Rome and mother Volumnia discover the difficulty of taming it.

At first the general acquiesces to the civilians, but provoked by the tribunes

of the people, he loses control over himself altogether, insults them so

intemperately that he is banished for treason, and ends up joining the enemy

Volsicans, allowing his hatred of the plebs to extend to hatred of his own

family. As he threatens revenge against the whole city of Rome in the last act,

peace is given a second chance. At her son's tent in the camp of the besieging

army, Volumnia abjures both force and policy and invokes the agency of mercy:

"Our suit /is that you reconcile them: while the

Volsces/May say 'this mercy we have showed' the Romans/This we received;' and

each in either side/give the all-hail to thee, and cry 'Be blest/for making up

this peace.'"

This conversion scene of recognition and

reversal displays the mother's ability to pacify her son with the persuasive

force of language. The power of her love overcomes his hate, just as the power

of her eloquence overcomes his refusal to speak:

"Coriolanus [holds her by the hand silent]:

Mother, mother O/you have won a happy victory to Rome; /But for your

son.../Most dangerously hast thou with him prevailed/If not most mortal to

him....I'll frame convenient peace" ... Ladies, you deserve/To have a

temple built you. All the swords /In Italy, and her confederate arms,/Could not

have made this peace" (5.3.183-209).

The cruel warrior has been transformed into a merciful

emissary of peace who will approach the Volsicans with humility and tact,

subordinating his own mixed feelings to the requirements of his diplomatic

mission. The dramatic climax of

Shakespeare's play enacts James' emblem: the triumph of Eirene over Mars.

Such hoped-for outcomes guided James'

foreign policy, as he negotiated armistice between the Low Countries and Spain

and marriages of his children into both Protestant and Catholic royal families.

The shift of Shakespeare’s clout from

supporting a hawkish worldview to supporting the outlook of a peacemaker can be ascribed to a desire to please

his sovereign. After all,

Elizabeth I commissioned the acting company he wrote for and held stock in as

The Queen’s Men and James commissioned it as The King’s Men. But on the basis of my readings of the plays, I’d argue that

after 1599, Shakespeare's own abhorrence of war became steadily more emphatic

and that his enthusiastic support for James stemmed at least partially from a

personal desire to further the king's peacemaking mission. It is true that

after Shakespeare's death, James' continuing endeavors in this cause could not

forestall the tragic outbreaks of either the Thirty Years War, in the latter

days of his reign, or of the English civil war, during the reign of his son.

Nevertheless, by recovering the early Humanists' rejection of military

politics, culture, and ideology, both the mature Shakespeare and his royal

benefactor strengthened a fragile tradition that too often remains ignored or

denied.

When this essay was published in 1992, it seemed to be of

interest only to Shakespeare critics and Renaissance historians. But then came 9-11 and the buildup

leading to the second Iraq war. In

November 2002, I came across a website

affiliated with The Ludwig von Mises Institute, a libertarian think tank in

Atlanta Georgia.

http://www.lewrockwell.com/stromberg/stromberg46.html

- ref

The author, Joseph Stromberg, had discovered in this essay a correction to the appropriation of Shakespeare’s Clout by those he referred to as neocons and Whigs:

With so many high-toned writers these days recommending a return to the

warlike "wisdom" of classical thinkers and their Renaissance

interpreters, it is worth our while to look at other points of view.

I suppose this means that the long campaign against the

Stuarts was, at least in part, waged in behalf of Whig mercantilist

war-mongering and empire-building, as well as anti-Catholicism. And so much for

Whig history…

Then

last August I received an email from a young scholar in Minnesota who had

written a brilliant though highly partisan study of the Bush-Henry V

connection:

http://www.poppolitics.com/articles/2003-05-01-henryv.shtml

He

suggested we collaborate on organizing a panel for the 2006 annual convention

of the Shakespeare Association of America which brings together over a thousand

academic Shakespeareans. Since

then we have agreements to participate from David Perry, a professor who teaches

ethics at the U.S. Army War College, Nina Taunton, a British authority on 16th century military discourse, Kent Thompson, artistic director of the Alabama Shakespeare Festival, who has mounted a production of Macbeth funded by the Department of Defense to tour military bases,

and none other than Mr. Kenneth Adelman.

The title of the panel is: “Drafting Shakespeare,

the Military Theatre.” So here I hope is one answer to the question

posed by your Humanities Inquiry 2005—Why Shakespeare Matters.