Shakespeare Association of America Annual Conference

Philadelphia April 13 2006

Roundtable Panel Discussion: “Drafting Shakespeare: The Military Theatre”

Opening remarks by Steven Marx

Shakespeare against Militarism

I believe Shakespeare’s role in regard to the contemporary military should be to help expose and oppose the plague of militarism that infects American society.

Militarism is a recurrent theme in Shakespeare’s plays. Over the course of his career, his attitudes moved closer and closer to those articulated by influential pacifist humanists like Juan Vives, Thomas More, and Desiderius Erasmus and espoused by his patron, King James I.

I suggest three ways in which Shakespeare can be enlisted in the struggle against militarism.

First, he does a fine job in pointing the finger at those who Bob Dylan called the Masters of War.

How better to illuminate our present-day catastrophe in Iraq than to read Shakespeare’s version of the confidential advice King Henry IV gives to his son:

Be it thy course to busy giddy minds/ With foreign quarrels; that action, hence borne out,/May waste the memory of the former days.

Henry V’s invasion of France is mounted to consolidate a shaky and illegitimate hold on the throne at home and to plunder overseas. The clergy provide legal and religious justification in return for Henry’s opposition to a bill urged by the Commons that would strip the church of lands whose income could be used to support poor people who are sick and old.

Shakespeare’s exposure of these movers and shakers is backed by Erasmus’ observation:

There are those who go to war for no other reason than because it is a way of confirming their tyranny over their own subjects. For in times of peace the authority of the council, the dignity of the magistrates and the force of the laws stand in the way, to a certain extent, of the prince’s doing just what he likes. But once war has been declared, then all the affairs of the State are at the mercy of the appetites of the few. Up go the ones who are in the prince’s favour, down go the ones with whom he is angry. Any amount of money is exacted. Why say more? It is only then that they feel they are really kings.

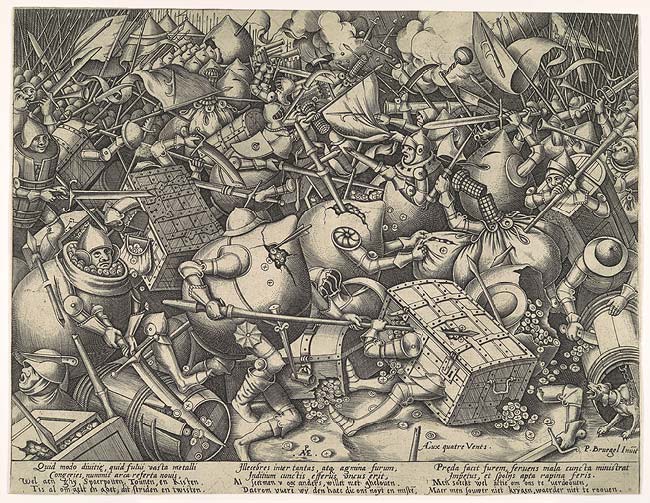

This appears in his essay of 1515 entitled, Dulce Bellum Inexpertis, that is “Sweet is war to those who haven’t experienced it.” [cited by Janet Spencer, "Pirates, Princes and Pigs: Criminalizing Wars of Conquest in Henry V." Shakespeare Quarterly 47,2 (Summer 1996 160-67)]

A second way that Shakespeare can be enlisted to oppose militarism is in debunking the ideals of a professional military class. In the plays he produced after 1603, those ideals are critiqued and ridiculed. Troilus and Cressida bitterly mocks the classical heroes of the Trojan war as windbags, egomaniacs and cowards and shows the rationales for war on both sides to be self-serving, futile and irrational. Othello, Macbeth and Coriolanus, the three charismatic hero-generals of the late tragedies, at first are propped up by military character-armor, but they succumb to clearly-diagnosed moral and psychological ailments largely traceable to their dependent relationships with wives and mothers.

A third way that Shakespeare can be enlisted to oppose militarism is through his representation of the soldier or the common person as “a pawn in their game.” Countering the deceit of “Be all you can be,” or “an army of one” trumpeted by today’s recruiting officers, Falsfaff scoffs, “Tut, tut; good enough to toss; food for powder, food for powder; they'll fill a pit as well as better.” “The little touch of Harry in the night” from which, the chorus of Henry V claims “every wretch…beholding him plucks comfort,” doesn’t allay the footsoldier’s despair:

But if the cause be not good, the king himself hath a heavy reckoning to make, when all those legs and arms and heads, chopped off in battle, shall join together at the latter day and cry … some swearing, some crying for a surgeon, some upon their wives left poor behind them, some upon the debts they owe, some upon their children rawly left.

I’ve spoken of enlisting Shakespeare to help oppose militarism, but the title of this SAA panel speaks of drafting him. As its originator Scott Newstok has demonstrated in his article, “George W as Henry V,” Shakespeare has been forcibly conscripted into the service of militarism by the generals and the pundits. In his book, Shakespeare in Charge: The Bard’s Guide to Leading and Succeeding on the Business Stage, Kenneth Adelman reads Shakespeare’s account of the war against France as follows:

The family business has not been going well. Henry’s father, Henry IV had a woeful reign notable for rebellion …. His advice to his son was succinct: Go for an acquisition, even if it entails a hostile takeover. In fifteenth century England that meant finding someplace to attack—it didn’t much matter where—in order to ‘busy giddy minds’ at home ‘with foreign quarrels.’ Like any new and especially young executive, Henry longs to make his mark. War offers a great opportunity to do so—but only if he wins. (p.4)

The sinister strategy Shakespeare brings to light here is presented by Mr. Adelman as exemplary to those who benefit from war—the leaders and succeeders in charge today who regard the nation born in this city of brotherly love as their family business. The book’s co-author, Norman Augustine, is CEO of Lockheed Martin, one of the largest arms manufacturers and defense contractors in the world. And Mr. Adelman, among his many other leadership roles, sits on the Defense Policy Board, which traditionally served to strengthen ties between the private sector and the Pentagon, and which contributed significantly to our present administration’s disastrous middle-east foreign policy. Indeed, war provides “great opportunity” for these people--win or lose, and “it [doesn’t]… much matter where.”

Erasmus was recognized as the greatest scholar and thinker of early Renaissance Europe. He was given a seat at the tables of the Great, who were tutored by humanists and loved their culture. Erasmus tried to persuade the Movers and Shakers to give up their bellicose power games and to devote themselves to the protection and welfare of all their subjects. The policies that he championed—outlawing war, arbitrating international disputes, disbanding standing armies--never took hold. But his voice still speaks, along with Shakespeare’s, to guide and inspire those engaged in a battle of true worth.