Puer Eternus:

The Pastoral of Youth

Ambo florentes aetatibus, Arcades ambo 1

Though pastoral presents itself as a celebration of rural over urban, the bucolic fiction of another, better world has always served as a vehicle to glorify more than country life. The very persistence of this fiction results largely from its ability to disguise longings too subversive of dominant social values to be straight-forwardly expressed. The most prevalent of such Arcadian aspirations is the ideal of innocence. In the words of Alexander Pope:

The first rule of pastoral [is] that its idea should be taken from the manners of the Golden Age and the moral be formed upon the representation of innocence.2

Itself a charged and problematic notion, "innocence" has inspired painters, musicians and poets, as well as preachers, hucksters and pornographers to depict worlds that "represent" its meaning. The Arcadian realm overlaps with the Garden of Eden, the Golden Age, the Elysian Fields and with many early accounts of the New World as an elaboration of that ideal, a vision of a natural utopia free of the corruption of historical civilization. Whether or not they are inhabited by shepherds, all these places are pastoral in that they project a world of innocence.

The representation of innocence invokes the spectre of a lost past. Eden and the Golden Age lie buried in prehistory. The happy savages of the New World preserve the departed way of life of the ancestors of Europeans. The atmosphere of bittersweet longing which suffuses the groves and meadows of Arcadia conveys a sense of former beauty destroyed by the passage of time. The landscape and the type of culture that pastoral memorializes has suffered the encroachment of ruthless historical forces: war, urbanization, economic development, exploitation, enclosure, absentee landlordism and ecological disaster. In this respect the mode expresses a valid social concern for the decline of rural values and the destruction of

22

nature. But in fact, the good old days before the demise of country life elegaically recalled by the pastoralists usually turn out to be the days of their own youth-whether they transpired in the twentieth, the sixteenth or the first century.3

Until the present era, many writers and readers of pastoral grew up in rural areas before moving to cosmopolitan centers to find colleagues, stimulation and non-rustic means of support. They therefore tended to equate their sense of the golden years of childhood with idealized memories of country life:

Whilome in youth, when flowrd my ioy full spring Like Swallow swift I wandred here and there: For heate of heedlesse lust me so did sting, That I of doubted daunger had no feare. I went the wastefull woodes and forest wyde Withouten dreade of Wolues to bene espyed... For ylike to me was libertee and lyfe.4

The lost past celebrated and mourned in pastoral is in fact what Renaissance writers often called the Golden Age: "the Worldes Childhoode."5 For, as Sir Walter Ralegh noted in his History of the World:

... our younger yeares are our golden Age; which being eaten up by time, we praise those seasons which our vouth accompanied: and (indeede) the grievous alternations in our selves, and the paines and diseases which never part from us but at the grave, make the times seeme so differing and displeasing: especially the qualitie of man's nature being also such, as it adoreth and extooleth the passages of the former, and condemneth the present state how just soever.6

Following Ralegh's observation, this chapter argues that pastoralists' idealizing of innocence-their exaltation of rural over urban, nature over art, simple over sophisticated-expresses a preference for the life stages of childhood and youth and a consequent antipathy toward the condition of adulthood. The pastoralists' revolt against civilization is largely a rejection of the demands and the compromises of maturity; their utopian counterculture is in fact a youth culture; and their nostalgia for

23

a more primitive state of society often disguises a longing for their own lost childhood. This thesis implies a corollary interpretation of the most common pastoral conventions. The shepherd swain represents the figure of youth itself, the central theme of love represents specifically young love, and the dominant pastoral setting of the locus amoenus, the pleasant spot of eternal springtime, represents a vision of childhood that will never pass.

Assertions similar to these have been made before. Other writers have observed the convergence between the pastoral ideal of innocence and the glorification of childhood. However, no one has proposed, as I do here, to use the Protean concept of "youth" to illuminate the web of relations connecting pastoral conventions with various systems of thought-systems of literary genre, psychic archetypes, developmental stages and social stratification. Perceiving that web can deepen an understanding of what pastoral is all about and can enrich readings of many individual works. It can also refine knowledge of cultural history. During the last twenty five years, interest in the ideals of youth and childhood has flourished among researchers in a variety of fields. A historian of ideas has written a book on The Cult of Childhood as one strain of philosophical primitivism; a social historian has written about Childhood and Cultural Despair, and a large bibliography of work by psychohistorians has analyzed changing conceptions and roles of youth during the period 1500 to 1800. And yet, among all these writers, mention of the pastoral mode remains conspicuously absent.

Perhaps the overlooked connection is attributable to the tendency to exaggerate periodization and discontinuity in both social and literary history. Like the author of The Image of Childhood, most people associate the apotheosis of childhood exclusively with the Romantics and their descendants:

Until the last decades of the eighteenth century, the child did not exist

as an important and continuous theme in English Literature . . . With

Blake's "Chimney Sweeper" and Wordsworth's Ode on "Intimations of

24

Immortality," we are confronted with something essentially new, the phenomenon of major poets expressing something they considered of great significance through the image of the child.7

It is true, as George Boas points out, that the primitivism that equates the artist with the child and sets both in opposition to the philistine bourgeois adult is a leitmotif from Blake to Lawrence, from Schiller to Rilke:

Die Kindheit ist das Reich der grossen Gerechtigkeit und der tiefen Liebe ... Entweder es bleibt jene Fuelle der Bilder unberuehrt hinter dem Eindringen der neuen Erkenntnisse, oder die alte Liebe versinkt wie eine sterbende Stadt in dem Aschenregen dieser unerwarteten Vulkane. Entweder das Neue wird der Wall, der ein Stueck Kindsein umschirmt, oder es wird die Flut, die es ruecksichtslos vernichtet, d.h. das Kind wird entweder aelter und verstaendiger im buergerlichen Sinn, als Keim eines brauchbaren Staatsbuergers, es tritt in den Orden seiner Zeit ein und empfaengt ihre Weihen, oder es reift einfach ruhig weiter von tiefinnen, aus seinem eigensten Kindsein heraus und das bedeutet, es wird Mensch im Geiste aller Zeiten: Kuenstler.8

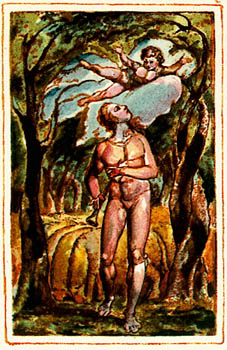

But both Coveny and Boas ignore the fact that pastoralists have expressed ideas like these since the time of Theocritus. Most of his herdsmen are youths, and the sensibility in all the Idylls is pointedly childlike.9 Many of the singers of Vergil's eclogues are adolescents, and even his old shepherds are referred to as pueri-boys. During earlier times, "The Cult of Childhood" has in fact a literal as well as figurative meaning, since the puer eternus-the boy god-often dominates fertility rituals which identify his eternal rejuvenation with the rebirth of the spring.10 The central pastoral themes of youth and vegetation combine to draw this literary tradition within the orbit of initiation rites, occult symbols and millenarianism. The orbit extends from the Eleusinian predecessors of Theocritus' Daphnis to the medieval mystic, Joachim of Flora's vision of the end of history as the transfiguration of all humanity into the state of boyhood." It also includes Renaissance neoplatonists who used the figure of the young swain to represent an initiate into spiritual-erotic mysteries.12 The shepherd boy is the child

25

of the imagination that the Romantics and the moderns equate with the spirit of the artist. As David Wagenknecht has insisted, "...pastoralism is the great unexplored link between Romantic and Renaissance ideas."13 It is largely through the vision of innocence that this link is forged.

In what follows, I expand that vision of innocence by plaiting the three thematic strands mentioned in the introduction: a) recurrent pastoral motifs, b) primitivistic ideals of the good life in a better world, and c) concepts of childhood or youth as an admirable human state. Beginning with customs extrinsic to the poetry itself, I show how literary tradition stipulates pastoral to be the poet's youth-work, while the pastoral theme of rustic festivity coincides with the social practise of rural youth groups in Renaissance England. Then, moving into the texts, I delineate the essential conventions of bucolic character, theme and setting which project ethical, aesthetic and erotic ideals associated with childhood. I conclude the chapter by demonstrating that when adult writers include pastoral interludes in the larger context of epic or drama, they are generally portraying a regressive return to the state of childhood innocence-a return regarded as both solace and threat.

Within the overall plan of my study, this exploration of pastoral innocence supplies thematic background for my later examination of the pastoral debate of youth and age-a literary convention which provides a key to interpret Spenser's The Shepheardes Calender, The present chapter therefore leads into the next chapter's parallel treatment of the contrary ideals of experience in the pastoral of old age. But the pastoral of youth also rewards attention for its own sake, not only as a link between the Renaissance and Romanticism, but as a universal strain of sensibility. The ideal of childhood remains an archetypal theme, as timeless as the celebration of the garden. The holy child, in the words of C.G. Jung, is "bigger than big, smaller than small." It appears in the earliest and most widespread of religious myths as the bearer of special powers and as

26

the symbol of the transition between the secular world of the conscious adult self and the unknown but intuited world that lies beyond:

The "child" is therefore renatus in novam infantiam. It is thus both beginning and end, an initial and a terminal creature. The initial creature existed before man was, and the terminal creature will be when man is not. Psychologically speaking, this means that the "child" symbolizes the preconscious and the post-conscious essence of man. His preconscious essence is an anticipation by analogy of life after death ... The child had a psychic life before it had consciousness. Even the adult still says and does things whose significance he realizes only later, if ever. And yet he said them and did them as if he knew what they meant. Our dreams are continually saying things beyond our conscious comprehension . . . We have intimations and intuitions from unknown sources. Fears, moods, plans, and hopes come to us with no visible causation. These concrete experiences are at the bottom of our feeling that we know ourselves very little; at the bottom too, of the painful conjecture that we might have suprises in store for ourselves. 14

The young Elizabethan poet started his career by writing pastorals. He did so not only because his grammar school study of Latin and his first exposure to literature was by way of the Eclogues of Mantuan and the Bucolics of Vergil.15 Any writer who aspired to join the illustrious company on the heights of Parnassus knew that his ascent should start in the vales of Arcady. An ancient decorum demanded that the first fruits of literary labor take the form of pastoral. In the introduction to his first published work, Spenser thus addresses The Shepheardes Calender:

Goe little booke: they selfe present,

As child whose parent is unkent...

And asked who thee forth did bring

A shepheards swaine say did thee sing ... 16

The humble pose of shepherd swain symbolized both rusticity and youth. The budding poet, "who for that he is

27

Unkouthe ... is unkist, and unknowne to most men. affects the diffidence equally appropriate to bumpkin and debutant. In the commendatory epistle, E.K., Spenser's apologist and commentator, provides a full explanation of the connection:

Which moved him rather in Aeglogues, then otherwise to write doubting perhaps his habilitie ... following the example of the best and most ancient of Poetes, which deuised this kind of wryting, being both so base for the matter, and homely for the manner, at the first to trye theyr habilities; and as young birdes, that be newly crept out of the nest, by little first to prove theyr tender wyngs, before they make a greater flyght. 17

The posture of rustic humility displays the prudence and caution of the petitioner and at the same time the young man's anything but humble claim to a noble lineage:

So flew Virgile, as not yet well feeling his winges. So flew Mantuane being not full somd. So Petrarque. So Bocace; so Marot, Sanazarus, and also diuers other excellent both Italian and French Poetes, whose footing this Author euery where followeth, ...So finally flyeth this our new Poete, as a bird whose principals be scarce growen out, but yet as that in time shall be able to keepe wing with the best. 18

By adhering to the Vergilian "Perfecte Pattern" of a poet's career, the pastoralist undertakes the youthful apprenticeship that may eventually permit him entry into the guild. Following the generic models established by past masters, his first work falls within strict limitations of scope, length, subject matter, diction and tone. Implicitly, however, the writing of pastoral expresses the poet's intention to address himself to some "higher argument" at a future time. The pastoral product itself can be regarded as a kindof "inaugural dissertation"--a proof of ability to proceed.

In this sense, pastoral Juveniles form the literary equivalent of their creator's youth. Once the initial offering is accepted, the writer sloughs off the bucolic role like a snakeskin and looks back upon it as an earlier phase of his own development:

28

And even as up to this point you have fruitlessly spent the beginnings of your adolescence among the simple and rustic songs of shepherds, so hereafter you will pass your fortunate young manhood among the sounding trumpets of the most famous poets of your century, not without hope of eternal fame.19

Thus predicts the seer in Sannazaro's Arcadia, though its author never did go on to write epic or drama. Spenser, on the other hand, like Milton, Pope, Blake and Wordsworth followed the curriculum faithfully. At the end of The Shepheardes Calender, Spenser's pastoral persona, Colin Clout, hangs up his oaten reed and bids the herdsman's world adieu. At the opening of The Faerie Queene-the major accomplishment of his majoritySpenser announces his own metamorphosis:

Lo I the man, whose Muse whilome did maske,

As time her taught, in lowly Shepheards weeds,

Am now enforst a far vnfitter taske,

For trumpets sterne to chaunge mine Oaten reeds,

And sing of Knights and Ladies gentle deeds.20

Though the writer at this point still feels himself "unfit" for the task ahead, he accepts his Muse's command to renounce the pastoral role "enforst" by his youth, and resolutely steps forward to accept the part of courtier and epic poet.

The "Knights and Ladies' gentle deeds" that the adult poet will sing are performed in a broader and more consequential arena than the rural landscape of the shepherd swain. Rather than the natural world of cyclical recurrence or the private world of thoughts and feelings, it is the public sphere of grand personages, heroic acts and cataclysmic events. The distinction between the setting and subject matter of the major genres and the world of pastoral corresponds to a difference in the actual

concerns and experiences of maturity and youth. By its very nature the public, active life is adult, while the private, natural world is a protected domain of the young.

Pastoral's affirmation of nature and rustic life also converges with youth in the social institutions of holiday festivity. Among

29

the features of rural existence eroded by the growth of mercantile civilization, the decline of seasonal celebrations evoked some of the strongest nostalgia from the poets and their audiences:

Happy the age and harmelesse were the dayes For then true love and amity was found

When every village did a May Pole raise And Whitson-ales and MAY-GAMES did abound.21

The urban readers of Elizabethan poetry went back to the country for holiday escape from the rigors or the boredom of everyday routines.

Hey ho, to the green wood now let us go

Sing heigh and hey ho.22

Come away, come sweet love, the golden morning brekes

All the earth, all the ayre

of love and pleasure speaks.23

The "other world" to which they came away for a feeling of rejuvenation lay beyond the city walls, outside civilized matrices of order and meaning. The natural wilderness teemed with the vitality of youth:

Every bush now springing

Every bird now singing,

Merily sate poore Nico

Chanting tro li lo

Lo lilo li lo

Till her he had espide,

On whome his hope relide

Down a down a down

Down with a frown

Oh she pulled him down.14

The poetic motif of reverdie, or regreening, which introduces so much Middle English poetry and retains its popularity in Tudor

30

pastorals, expresses the unity of natural and human rhythms. The flowing of the water and warming of the earth in the mineral world correspond to the movement of sap and swelling of buds in the vegetal world and to the stirring of the animal spirits in the creatures of the field and in the hearts of "Yonge folke":

The merrymakers took to the woods as foresters, returning thence with the May Pole. A King and Queen of the Forest, or Lord and Lady of the May, were chosen to impersonate Robin Hood and Maid Marion. This couple presided over the pastimes on the village green ... The sportsthe archery contests, bouts at quarterstaff, wrestling for the ramculminated in a ritual of initiation. To join the band of merry men and to wear Lincoln green was to renew one's contact with nature. To give a lass "a green gown" was to tumble her in the grass. The may-games, with their morris dances and hobby horses could be not only rough but frankly carnal. 2-1

In European peasant societies of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, adolescents were designated as the custodians of these rural festivities.26 People of all ages who participated in the revels of May were permitted to act childishly, but the young folk were in charge:

Is not thilke the very moneth of May

When love lads masken in fresh aray?...

For thilke same season, when all is ycladd

With pleasaunce; the grownd with grasse, the Woods

With greene leaves, the bushes with bloosming Buds.

Yougthes folke now flocken in every where,

To gather may buskets and smelling brere.27

The organization was carried out by institutionalized youth groups known as Charivari or Abbeys of Misrule .28 Such parish institutions sponsored the rituals which expressed unruly youthful instincts-on the one hand giving them vent and allowing them to kindle and energize the rest of the community, and on the other, containing and restricting them within broadly acceptable limits.

31

The rural festive periods were characterized by Saturnalian reversals of all sorts. Masters would exchange authority with their servants and youth would take dominance over age.29 In Spenser's "May" eclogue, Palinode describes how the Church hosted pagan ceremonials and the saints themselves got slightly tipsy:

And home they hasten the postes to dight, And all the Kirke pillours eare day light, With hawthorne buds, and swete Eglantine, And girlonds of roses and Sopps of wine. Such merimake holy Saints doth queme (11-16)

These festivities did not elicit universal admiration, however. Piers replies to this invitation with a dose of cold water and tells his crony to grow up:

For Younkers, Palinode, such folies fitte But we be men of elder witt.

(18-19)

In rebuking his friend's nostalgia for the unrestrained liberty of the revellers, Piers helps define the pastoral of youth by arguing the contrary perspective of age. The conflict between the two observers exemplifies a continuing public controversy about holiday festivity during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Piers' reply reflects a widespread Puritan disapproval of such Maying practises:

Against May, Whitsunday, or other time all the young men and maids, old men and wives, run gadding over night to the woods, groves, hills, and mountains, where they spend all the night in pleasant pastimes ... And no marvel, for there is a great Lord present amongst them, as superintendent and Lord over their pastimes and sports, namely Satan, prince of Hell... I have heard it credibly reported (and that viva voce) by men of great gravity and reputation, that of forty,

32

three score, or a hundred maids going to the wood over night, there have scarcely the third part of them returned home again undefiled. These be the fruits which these cursed pastimes bring forth.30

The Puritan attitude rested partly on objections to the release of animal instincts and partly on their aversion against the playful and hence childlike elements of both pagan and Catholic ritualism.31 The Puritans also objected because such regressive ventures into pastoral otium-holiday leisure-took valuable time away from the dutiful conduct of every-day business. Piers continues his invective:

Those faytours little regarden their charge...

Passen their time that should be sparely spent,

In lustyhede and wanton meryment...

I muse what account both these will make.

When great Pan account of shepherds shall aske.

(39-54)

He prefers the sensible, modern and adult routine of the urban merchant.

By the late sixteenth century, the youth groups that organized holiday misrule and regreening festivals were already an archaic country phenomenon. In the city, their social function died out with the rise of professional and guild associations structured along class and status, but not age-grade lines. According to N.Z. Davis, this persistence in the countryside of youth groups which united people across the borders of economic and social rank helps explain "how the peasant community defended its identity against the outside world."32 Thus, during the Tudor period, pastoral's vision of the country took on connotations of holiday escape and the aura of a declining way of life preserved in youth and by youth. But the association of the bucolic herdsmen with the child runs deeper than this historical circumstance; it permeates the texture of the poetry. The protagonist of English pastoral, who, in Sidney's words, "pipes as though he should never be old," invariably carries the epithet of "swain."33 The multiple denotations of

33

this word-"rustic," "shepherd," "young suitor," and "boy," build the identification of rural life and youth into the very language of the poet. For Vergil, whose eclogues Viktor Poeschl characterized as the expression of "a pure, childlike poet's soul," the equivalent term to "swain" is puer.34 This word signifies "herdsman," "menial laborer," and "boy." The shepherd thus represents the eternal boy, a stereotype of youth itself, which in other contexts has become known as the puer eternus.

This term originated with Ovid's address to lacchus, the child-god of the Eleusinian mysteries. C.G. Jung and his disciples used it to name an indispensable and compelling "archetype of the collective unconscious":

The child personifies the transcendant powers of the collective unconscious itself ... (it is) an avatar of the self's spiritual aspect ... The puer eternus figure is the vision of our first nature, our primordial golden shadow, our affinity to beauty, our angelic essence as messenger of the divine, as divine message.31

James Hillman expands this definition of the puer ideal by adducing the analogy of horizontal and vertical axes. The puer's prospensity is for flying and falling. Like E.K.'s poet-bird, or Icaros or Phaethon, he oscillates between the heights and depths of his "labile moods":

He is weak on earth, for he is not at home on earth or the horizontal space-time continuum we call reality. The puer understands little of work, of moving back and forth, left and right, in and out, which makes for subtlety in proceeding step by step through the labyrinthine complexity of the horizontal world.36

This account of the puer's emotional volatility, his alienation from "the world," and his capacity for spiritual transcendance complements descriptions of the figure of the pastoral swain. In his essay on Peter Pan and Alice in Wonderland as nineteenth century versions of pastoral, William Empson identifies the herdsman with a similar conception of the child, the human

34

being as yet uncorrupted by the repressive and distorting influences of custom and culture. The pastoral swain as child is also, according to Empson, the poet, the artist, the original genius whose access to natural instincts and to unconscious fertility provides a steady flow of creative inspiration. The notion is based on a feeling

... that no way of building up character, no intellectual system, can bring out all that is inherent in the human spirit and therefore there is more in the child than any man has been able to keep . . . the world of the adult made it hard to be an artist . . . they kept a taproot going down to experience as children...

The child, according to this line of thought, "possesses the right relation to nature which poetry and philosophy seek to regain."37

The constellation of shepherd and child plays a central role in traditional Christian iconography. In the gospels, the good shepherd Jesus portrays the innocence of his flock as an analogue for grace: those who would enter the kingdom of heaven must become like little children. Medieval mystics like Joachim of Flora, Meister Eckhart and St. Francis of Assisi described their own transfigured consciousness as that of a babe's at the breast, a milennial return to the Edenic garden. As the cult of childhood gained popularity in devotional literature during the seventeenth century, Nativity songs like Milton's "Ode," emphasized the traditional juxtaposition of baby Jesus, shepherds and livestock, and adopted the tone, imagery and diction of literary pastoral. In the poetry of Marvell, Crashaw, Traherne and even Robert Herrick, the lamb, the good shepherd, the Edenic Adam, and the puer eternus are superimposed in the figure of the bucolic swain playing his oaten flute:

Go prettie child, and beare this Flower

Unto thy little Saviour;

And tell Him, by that Bud now blown,

He is the Rose of Sharon known:

When thou hast said so, stick it there

35

Upon his Bibb, or Stomacher:

And tell Him, (For good hadsell too)

That thou hast brought a Whistle new,

Made of a clean straight oaten reed,

To charme his cries, (at time of need:)38

Once again, this pastoral of youth is set into relief by the response of the Puritans. Just as they opposed the ideal of innocence in holiday festivity, they had little patience with the notion of a holy primitive state. Like Calvin, who condemned unbaptized babies not to Purgatory or Limbo, but to Hell, and like Augustine, who dwelt on the malice of the newborn child, they believed more in original sin than original innocence. To Jesus' invitation, "Come little ones," the Puritans preferred St. Paul's injunction: "When I was a child I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things."39

Renaissance Neoplatonists also idolized youth in the figure of the shepherd, but they found in him an adolescent rather than an infantile quality of innocence: "It is the mentality of this age, the so-called aesthetic stage of life, that pastoral celebrates. Socrates calls it the 'beauty of the young, over whom the god of love watches'."40 Under the influence of the school of Ficino, Italian writers like Poliziano and Tasso used bucolic conventions to symbolize membership in an esoteric brotherhood of initiates. Whether or not, as Richard Cody claims, most Renaissance pastoral is really a cipher of hermetic doctrines of transcendance, the idealistic, passionate and agonizingly sensitive adolescent heroes of Aminta, Orphee, Sannazaro's Arcadia, and Garcilaso's Eclogues see the world from the puer's "Aesthetic point of view ... the world as beautiful images or as a vast scenario ... life become literature."41 Their home in the Woods represents no rustic crudeness, but a higher refinement, a world of feelings and ideas displaced from city and court. In their aetherial vulnerability, their humorless sincerity, and their cultivated alienation, these characters prefigure the Sturm und Drang heroes of nineteenth century romanticism.

36

Many of the spiritual ideals of the pastoral of youth reappear in Wordsworth's "Immortality Ode." As part of the narrator's meditation on the meaning of his own life cycle, the poem alludes to most of the themes considered thus far: the pattern of the poet's growth, nostalgia for a lost past, rural festivity, Christian devotion and Neoplatonism. The speaker begins with recollections of his early childhood as the pastoral stage of his life:

There was a time when meadow, grove and stream

The earth, and every common sight,

To me did seem

Apparelled in celestial light,

The glory and the freshness of a dream...

And all the earth is gay;

Land and sea

Give themselves up to jollity

And with the heart of May

Doth every Beast keep holiday;

Thou child of Joy

Shout round me, let me hear thy shouts, thou happy

Shepherd-boy.42

There follow the recognitions that he must leave this paradise behind as he takes roles on the "humorous stage" of adult social life, that he must travel inland from the immortal sea that brought him hither, that he must bear the earthly freight that custom loads on his soul. These recognitions bring on depression, which is then relieved by another episode of bucolic nostalgia. But after revelling in the fantasy of young lambs, the sound of pipes and the rejoicing of the Maying, the speaker concludes by affirming, or at least asserting, his faith in the value of adulthood. The mature person's "philosophic mind," he insists, not altogether convincingly, will console him for losing the childhood vision of "splendor in the grass and glory in the flower."

In "Auguries of Innocence," Blake also speaks of the capacity "To see a world in a Grain of Sand/And a Heaven in a wild

37

Flower." He attributes childhood's heightened power of sensation to the cleansed doors of perception that have been the gift of the shepherd since Theocritus:

Come sit we under this elm tree, facing The nymphs and Priapus there by the rustics' seat and the oaks. if you sing as once

I'll give you to milk three times a she-goat with twins; although she's two kids, she fills up two pails Plus an ivywood bowl fragrant with wax, two-handled, new made: you can still smell the chisel . . . 43

According to Thomas Rosenmeyer, Theocritus' herdsmen if not children, are protected by the same patterns that make the child's world familiar and pleasureable. The shepherd's range of understanding and reason is limited ... he is a perceiver of concrete sensations and beautiful things."44 This freshness of perception graces the Renaissance bucolic song:

And we will set upon the Rocks Seeing the shepheardes feede theyr flocks By shallow Rivers, to whose Falls Melodious birds sing Madrigalls.

And I will make thee beds of Roses, And a thousand fragrant poesies, A cap of flowers, and a kirtle, Enbroydred all with leaues of Mirtle.

A gowne made of the finest wooll,

Which from our pretty Lambes we pull,

Fayre lined slippers for the cold:

With buckles of the purest gold

A belt of straw, and luie buds

With corall clasps and Amber studs ... 45

Theocritus invented the inventory genre, "the single most effective and congenial device in the pastoral lyric. in order

38

to "document the discreteness of the herdsman's sensory experience and his detachment-in pleasure."46 The primitive pleasure of the senses associated with childhood presents as significant a pastoral ideal as the spiritual innocence ascribed to it by Christians and Platonists. Arcadia is a landscape of the body as well as of the mind.

Renaissance writers and painters found a favorite mythological motif in the Judgement of Paris. They depicted the future abductor of Helen of Troy in the guise of a shepherd awarding the golden apple to Aphrodite and turning his back on Hera and Athena. Mythographers saw in this motif a symbol of pastoral's identification with the vita voluptatis, the life of erotic pleasure, and its rejection of the lives of action and contemplation.47 In fact, sensual love comprises the most common of bucolic themes.

It is appropriate that the poetic mode which praises nature over art celebrates the biological drive that human beings share with plants and animals. The Renaissance critic Julius Caesar Scaliger theorized that herdsmen made love their chief occupation because of their scanty dress, their healthy and plentiful food and their proximity to beasts.48 Others have attributed pastoral's emphasis on love to the absence of competing concerns. In a world like the shepherd's, free from want, war, politics and social climbing, there is not much else to do. Pastoral amor, as Greg observed, is love in vacuo, love removed from its usual social context.49 Poggioli saw Arcadia itself as an erotic utopia projected and ruled by the Freudian Pleasure Principle, and W.H. Auden spoke of "Arcadian Cults of Carnal Perfection."50

As the expression of an outlook on life that is characteristically adolescent, the pastoral ideal exalts a particular kind of eroticism: Young Love. It excludes the complexities of social courtship, the domesticated and exploratory love of long-term relationships, the contractual-sacramental love of marriage, and the procreative, nurturing love of parenthood. Instead, it proposes the pleasure of the body as the state of innocence-a natural, simple condition of salvation that is itself childlike. The

39

pastoral ideal of young love takes a number of contradictory forms: a utopia of licentiousness, or one of chastity or a paradoxical combination of the two. But all the varieties of the ideal share the faith that such pleasure once existed in the

iginal unfallen condition of humanity remembered with or nostalgia and regret. This reading of pastoral relies upon the modern psycholo ical tenet that erotic pleasure itself is a type of release from th-~ constraint of civilization achieved only through a tempora

reversion to an earlier state of consciousness:

The proper carrying out of the sexual act and the enjoyment of it involves an ability to give way to the irrational, the timeless, the purely animal in one: it includes loss of individuality in a temporary fusion with another. it contains the potentiality of leaving behind the tensions of civilization as one loosens the bonds of reality to float again in the purely sensuous . . . The sexual act contains a definite and direct relationship to infantile relatedness to the mother, with a renewed interest in sucking, in odor, in skin eroticism and a reawakening of old forbidden desires to explore and play with orifices. So very much that has been forbidden and kept unconscious ... needs to be released. The very good sexual adjustment demands such abilities to reverse the socialization process-and yet to permit the individual to be secure in the feeling that the regression and reversal will be only temporary and not reclaim the self.51

A number of pre-Freudian precendents substantiate this vie of sexuality. From Hellenistic and Roman times, the god of lo was pictured in Cupid as a wanton and fleshly baby; ai paintings of the Golden Age show the dalliance of nak couples encouraged by the ministrations of teasing put "Know that love is a careless child," says the narrator

Ralegh's "Walsingham."

However, most earlier writers thought of the erotic age not infancy but as adolescence. Medieval preachers, noting t correspondence between the seven ages of man and the sev

52

deadly sins, equated lust with youth. In the seven acts Jaques' pageant in As You Like It, the lover, "Sighing lik furnace, with a woeful ballad/Made to his mistress' eyebrov

40

takes his part between schoolboy and soldier (11, vii, 148-9) "In youth is pleasure/In youth is pleasure," repeats the refrain of a popular Elizabethan ballad.53 The categorization rests largely on physiological fact: puberty heightens the differences between the sexes and brings on an acute increase of desire.54

As much as the intensity, it is the aesthetic quality of adolescent sexuality that makes it an ideal of the pastoral youth. This quality of freshness, delicacy and wonder distinguishes Fruelingserwachen, the spring awakening of the erotic, from the more familiar, self-aware and bounded sexuality of the adult. Spenser illustrates the distinction in his description of the beauty of the flower, the sexual organ of the plant:

Ah see who so faire thing does faine to see

In springing flowre the image of thy day

Ah see the Virgin Rose, how sweetly shee

Doth first peepe forth with bashfulf modestee

That fairer seemes, the lesse ye see her may

Lo see soone after, how more bold and free

Her bared bosom she doth broad display

Loe see soone after, how she fades, and falles away.55

In the curl of its unfolding but still involuted shape resides the particular beauty of the closed rose. Its perceptible form reveals loveliness, yet hides an imminent mystery. To the beholder, the early stage conveys an experience of pure potentiality in the promise of even greater pleasure. This is the aesthetic of pastoral innocence, and it can be translated into one of the meanings of the archetype of the puer: "an anticipation of something desired and hoped for."56 Once the flower opens and "bold and free/Her bared bosom she doth broad display," that particular quality is lost. The complete revelation reaches a limit; mystery and wonder dissipate; in sets decay. From the perspective of the pastoral of youth, it is irrelevant that the fall of the petals brings on the ripening of the fruit.

The aesthetic of youthful eroticism dominated the culture of the Renaissance, which often defined itself as a period of freshness and rebirth.57 It is manifest in painting: Botticelli's

41

Primavera and Birth of Venus; in music: the song books of Dowland, Campion and Morley; as well as in the lingering adoration of youthful bodies that permeates pastoral literature:

I saw one that I judged among these beauties the most beautiful. Her tresses were covered with a veil most subtly thin, from under which two bright and beautiful eyes were flashing, not otherwise that the clear stars are wont to burn in the serene and cloudless sky. Her features ... fill with desire the eyes that looked upon them. Her lips were such that they surpassed the morning rose; betwixt them, every time that she spoke or smiled, she showed some part of the teeth, of such an exotic and wondrous beauty that I would not have known how to liken them to anything other than orient pearls. From there descending to the delicate throat as smooth as marble, I saw on her tender bosom the small girlish breasts that like two round apples were thrusting forth the thin material; midway of these could be seen a little

path, most lovely and immoderately pleasing to look upon, which inasmuch as it terminated in the secret paths was the cause of my thinking about those parts with the greater efficacy.58

Inventories like this one from Sannazaro's Arcadia were often condemned by British moralists as typical Italianate lasciviousness. But most English poets embraced the southern influence. Hallett Smith notes that the quasi-pastoral genre of "Eroticmythological" Elizabethan poetry gains much of its appeal from similar highly charged pictorial descriptions of adolescent beauty.59 The opening passage of Marlowe's Hero and Leander blasons the bodily charms of its heroine, "Venus' Nun," and concludes with an evocation of infantile bliss:

Some say for her the fairest Cupid pyn'd

And looking in her face, was strooken blind.

But this is true, so like was one the other.

As he imagyn'd Hero was his mother

And oftentimes into her bosome flew,

About her naked necke his bare armes threw.

And laid his childlish head upon her brest,

And with still panting rockt, ther tooke his rest.60

(1, 37-44)

42

The most precious jewell of Hero's beauty resides in her maidenhead, the badge of innocence. Though wholly in love, she hesitates to surrender the instrument of restraint:

Ne're king more sought to keepe his diademe, than Hero this inestimable gemme. No marvel] then, though Hero would not yeeld So soone to part from that she deerly held. Jewels being lost are found againe, this never, 'Tis lost but once lost, lost for ever.

(11, 77-86)

This rhetoric of adoration doesn't discriminate between the erotic attraction of girls and boys. Instead it plays on the distinctly hermaphroditic flavor of young love:

Amorous Leander, beautiful and yoong,

...

His dangling tresses that were never shorne, Had they beene cut, and unto Colchos borne, Would have allur'd the vent'rous youth of Greece, To hazard more, than for the golden Fleece... His bodie was as straight as Circes wand, love might have sipt out Nectar from his hand Even as delicious meat is to the tast, So was his necke in touching, and surpast The white of Pelops shoulder. I could tell ye, How smooth his brest was, and how white his bellie, And whose immortal fingars did imprint, That heavenly path, with many a curious dint, That runs along his backe, but my rude pen, Can hardly blazon foorth the loves of men, Much lesse of powerfull gods...

(1, 51-71)

Such descriptions place the reader in a position of a voyeur, who, reminiscent of the guests at Pelops' feast, figuratively devours flesh with his hungry eyes. The emotional distance between observed and observer accentuates the contrast between innocence and experience, ignorance and knowledge. The watcher's pleasure is that of King Neptune, the senex

43

amans, whose aged coldness is inflamed by the heat of Leander's passion and who steals delight from watery contact with the helpless youth:

The god...

... clapt his plumpe cheekes, with his tresses played,

And smiling wantonly, his love bewrayed.

He watch his armes, and as they opend wide,

At every stroke, betwixt them would he slide,

And steale a kisse, and then run out and daunce,

And as he turnd, cast many a lustfull glaunce,

And throw his gawdie toies to please his eie

And dive into the water, and there prie

Upon his brest, his thights, and everie lim,

And up againe, and close beside him swim,.

(11, 181-90)

Pastoral often exhibits young bodies bathing-in the sea, in a fountain, or in a stream-to extend that contrast between the sensual cleanliness of the child and the degeneracy of the dirty old man peeking from the bushes. Sannazaro, for instance introduced this description of bathing sherpherdesses between the blason of the young girl and an account of the old god Priapus' rape of a nymph:

But seeing the sun mounted high and heat grown every intense, they (the group of shepherdesses) turned their steps toward a cool hollow, pleasantly chattering and jesting amongst themselves. Being arrived there shortly and finding living springs so clear that they seemed of purest crystal, they began to refresh with the chill water their beautiful faces, that shone with no ingenious artifice. By pushing their trim sleeves back to the elbow they displayed all bare the whiteness of their arms, which added no little beauty to their tender and delicate hands. For this reason we, grown yet more desirous of seeing them, without much delay drew near to the place where they were, and there at the foot of a great tall oak we took our seats in no determined order.61

The vision of innocent sexuality not only governs the aesthetic sensibility of the pastoral of youth, it generates a set of ideologies. The most common of these is the ideology of Free

44

Love-the theory that the good life is achieved in a utopia of unrepressed libido, a golden age of liberated pleasure when, in Tasso's words, "S'ei piace ei lice"-whatever felt good was right.62 This is a juvenile philosophy in a number of senses. It expresses a desire for sexual freedom typical of the frustrated adolescent shackled by taboos on premarital sex or by lack of a willing partner. His desire tends to be more generalized than individualized, and he has yet to experience any bitter consequence of promiscuity.

Pastoral's advocacy of free love is also youth-oriented insofar

as it locates sexual contentment in the social arrangments of the

childhood of the race. For the sexual primitivist, the develop

ment of civilization is a Fall from Paradise, a history of

suppression of the native desires of the body. He finds a

prelapsarian state in the archaic ways of non-urban societies

where natural instinct is allowed to rule. The medieval eclog

form of Pastourelle is plotted on the assumption that any

peasant lass by definition is receptive to the proposal of country

pleasures.63 The Elizabethan lyric that celebrates the outriding

to the green world reflects actual Maying practises but also

9

gives vent to the fantasy of rural licence:

Come shepherds, come!

Come away

Without delay, Whilst the gentle time doth stay. Green woods are dumb, And will never tell to any Those dear kisses, and those many Sweet embraces that are given; Dainty pleasures, that would even Raise in coldest age a fire, And give virgin-blood desire.

Then, if ever

Now or never,

Come and have it: Think not I Dare deny

If you crave it.64

45

A

In the "quest for Paradise" that Renaissance adventurer embarked upon in their voyages of discovery to the New World, they found primitive societies whose apparent sexul freedom confirmed the myth of Edenic innocence.65 FrOD Montaigne's "Essay on Cannibals" to Diderot's Supplement a Voyage de Bougainville, old world commentators perceived in native cultures a way of life where love was unhampered by guilt or restraint:

... au moment oU le mSle a pris toute sa force, oU les sympt6mes virils

ont de la continuite ... au moment oU la jeune fille se fane s'ennuie, et

d'une maturite propre a concevoir des desirs, A en inspirer et A les

satisfaire avec utilite, ... L'un peut solliciter une femme et en etre

sollicite; l'autre se promener publiquement le visage decouvert et la

gorge nue, accepter ou refue les caresses d'un homme; . . . C'est une

grande fete . . . Si c'est une fille, de la cabane, et I'air retentit pendant

toute la nuit du chant des voix et du son des instrumens ...On deploie

l'homme un devant elle sous toutes les faces et dans toutes les attitude.

Si c'est un garqon, ce sont les jeunes filles qui font en sa presence les

frais et les honneurs de la fete et exposent A ses regards la femme nue

sans reserve et sans secret. Le reste de la ceremonie s'acheve sur un lit

de feuilles ...66

This dream of an original condition wherein what Blake called "an improvement in sensual enjoyment" brings a restoration of the state of innocence has repeatedly been translate(. from pastoral myth into the reality of chiliastic social and religious movements. From the twelfth until the eighteenth century, the "Brethren of the Free Spirit" established secrer pantheist congregations throughout Europe whose member claimed literally to return to Eden through the practise of nudism and promiscuous sex.67 Wilhelm Fraenger has convincingly argued that the vision of le ions of blissful orgiasts cavorting in the groves, pools and watercourses of Hieronymus Bosch's painting known popularly as "The Garden of Earthly Delights," illustrates the doctrine of this Arcadian cult.68 At the center of the garden flows the Fountain of Youth.

The pastoral ideology of free love has also found expression in a more secular libertinism. In what Frank Kermode refers to

46

as "Jouissance poetry,"69 seventeenth century writers like St. Amant, Thomas Stanley, John Wilmont and Thomas Carew uttered their nostalgia from the primitive state "when all women were for all men, and all men were for all women" with an undertone of rakish cynicism:

Thrice happy was that Golden Age

When compliment was constru'd Rage,

And fine words in the Center hid; When cursed NO stain'd no Maids Blisse, And all discourse was summ'd in Yes

And nought forbad, but to forbid.

The cavalier poet inverts the ideal of natural purity with a self-ironic sarcasm. But no matter how sophisticated his tone, the sexual adventurer too is driven by the thirst for innocence, for a resting place that will satisfy the infantile yearnings of the puer inside him. Witness the title and the selling points of a publication like Playboy, it is evident the fantasies of Arcadia and of pornotopia often overlap. Members of Fanny Hill's Swinger's club called themselves "restorers of the Golden Age," and many a present day "adult entertainment center" goes by the name of "Garden of Eden."

The most effective and influential statement of the ideology of free love occurs as a chorus in Tasso's pastoral drama Aminta:

0 happy Age of Gould; happy houres;

Not for with milke the rivers ranne,

And hunny dropt from ev'ry tree;

Nor that the Earth bore fruits, and flowres,

Without the toyle or care of Man...

But therefore only happy Dayes,

Because that vaine and ydle name, That couzning Idoll of unrest, Whom the madd vulgar first did raize, And call'd it Honour, whence it came To tyrannize oe'r ev'ry brest,

Was not then suffred to molest

47

Poore lovers hearts with new debate;

More happy they, by these his hard

And cruell lawes, were not debarr'd

Their innate freedome; happy state;

The goulden lawes of Nature, they

Found in the brests; and them they did obey,

Amidd the silver streames and floures,

The winged Genii then would daunce,

Without their bowe, without their brande;

The Nymphes sate by their Paramours,

Whispring love-sports, and dalliance,

And joyning lips, and hand to hand;

The fairest Virgin in the land

Nor scornede, nor flor'yed to displaye

Her cheekes fresh roses to the eye,

Or ope her faire brests to the day,

(Which now adayes so vailed lye,)

But men and maydens spent free houres

In running River, Lakes, or shady Bowres.71

To symbolize sexual innocence, Tasso here uses the same cluster of metaphors-Virgin/Rose/Breast-that Spenser later adapted to convey the aesthetic attraction of youthful eroticism. But there is a discrepancy between the two rhetorical figures. The veiled, suggestive beauty of the budding rose, whose allure Spenser's singer heightens to the detriment of the exposed bloom, represents teasing sexual decadence to the speakers of Tasso's chorus. Their ethos finds healthy, carnal affirmation in a bosom bared to the sunshine and nothing

positive in coyness, withdrawal, and hesitancy.

This descrepancy reflects a difference between the aesthetics of primitivism and its ideology. The beauty of sexual innocence depends on unfulfilled desire. It is born, as Plato said of love itself, from the union of Poverty and Plenty. The liberation of Free Love, on the other hand, postulates a Gratified Desire that tends to disappear by very virtue of its fulfillment. Indeed, by the end of the Aminta, Tasso's protagonist has grown up enough to learn the value of the honor and the chastity that was earlier rejected.

48

The pastoralist often conflates the diverging aesthetic and ideological affirmations of sexual innocence into a logically unstable but nevertheless compelling ideal: the free love of youth itself. Such an ideal superimposes the dichotomy of nature and civilization upon the dichotomy of youth and age, assuming no distinction whatever between the stages of adulthood and old age, treating them both as a single "other," hostile to youthful energy. The Age of Gold becomes the perfect state when the awakening sexuality of youth is neither controlled nor exploited by adults and their social order, but instead is allowed to flower freely in its own natural setting:

A Little GIRL Lost

Children of the future Age Reading this indignant page; Know that in a former time, Love! sweet Love! was thought a crime.

In the Age of Gold They agree to meet,

Free from winters cold: Tired with kisses sweet

Youth and maiden bright, When the silent sleep

To the holy light, Waves o'er heavens deep;

Naked in the sunny beams And the weary tired wanderers

delight. weep.

Once a youthful pair To her father white

Fill'd with softest care: Came the maiden bright:

Met in garden bright, But his loving look,

Where the holy light, Like the holy book,

Had just removed the curtains All her tender limbs with terror

of the night. shook.

There in rising day, Ona! pale and weak!

On the grass they play: To thy father speak:

Parents were afar: 0 the trembling fear!

Strangers came not near: 0 the dismal care!

And the maiden soon forgot That shakes the blossoms of my

her fear. hoary hair.72

Blake's version of the Golden Age includes both the attraction of purity and the release of freedom. Free love is the innocence

49

of the child. Freedom and innocence are destroyed together by the aged man whose holy book signifies the repressive law of civilization-a law which in other Songs of Experience takes the form of chartered streets, urban blight, and whip-wielding schoolmasters. Tasso's "Honore" here has become the greybeard father and the priests who turn the garden of love into a cemetery.

I went to the Garden of Love And saw what I never had seen: A Chapel was built in the midst, Where I used to play on the green.

And the gates of this Chapel were shut,

And Thou shalt not, writ over the door;

So I turned to the Garden of Love,

That so many sweet flowers bore,

And I saw it was filled with graves,

And tomb-stones where flowers should be:

And Priests in black gowns, were walking their rounds,

And binding with briars, my joys and desires.73

In setting lusty youth against crabbed age, Blake adopts the convention of pastoral debate which he is likely to have first discovered in his reading of The Sherpheardes Calender, but

which originates in the medieval conflictus.74 In his later prophetic

writings, affected by the experience of the American and French

revolutions, Blake extended the debate over sexuality to a larger

mythical framework. The young figure of Orc, representing

revolutionary energy itself, grows out of the pastoral motifs of child, sex

and nature. Orc wars perpetually against the aged Urizen, who

represents the Priests and Beadles of Civilization and their

authoritarian, rationalistic Newtonian order. The ultimately epic struggle

between innocence and experience, puer and senex, energy and order,

eros and civilization germinates as the central drama in the garden of

pastoral.

50

One might expect longing for the past and sexual attraction for innocence to appeal primarily to older people whose youth has left them. But in fact, this kind of pastoral has always been most popular among "the younger sort," as Gabriel Harvey observed in his report of the immense interest shown in Hero and Leander and Venus and Adnonis at the beginning of the seventeenth century.75 Indeed, adolescence is the most nostalgic of ages. The young man in his teens and early twenties has the greatest appreciation for innocence because he is in the midst of losing it. At one moment he may feel like the victim, at the next like the mourner; he is both pristine maiden and dirty old man, both coltish stud and prudish parson. This ambivalence stems from the developmental process itself, especially the process of sexual maturation. On the one hand desire signals growing up: aggressiveness, self-confidence, status, the power to beget children. On the other, the emergent sexual drive stimulates regressive longings for dependence, passivity, and all-enfolding bodily pleasure, for it reopens the possibility of infantile gratification forgotten during the latency period of late childhood.

And yet the nostalgia for a state of untrammelled sexual freedom can modulate abruptly into its opposite: a nostalgia for asexuality, for the very departing condition of childhood which prevailed before desire ever reared its seductive and threatening head. To the adolescent, the prepubertal age also appears as a lost paradise, for it is free of the emotional and moral conflicts of sexual maturity and because it antedates the coarsening of the skin, the growth of the beard and the deepening of the voice. The pastoral of youth projects a green Edenic world to signify chastity as well as liberty. From the perspective of adolescence, either provides a "better world"--an innocent alternative to its own dilemmas.

The same garden of love that Blake's speaker sees spolied by a thorny hedge and a barricaded chapel, according to Christian iconography, betokens the ideal of the Hortus Conclusus or "Enclosed Garden" of the Virgin Mary's pristine body:

51

I speake not of the Garden of Hesperides ... nor yet of Tempe, or the Elizian fields. I speake not of Eden, the Earthlie Paradice . . . But I speake of Thee, that GARDEN so knowne by the name of HORTUS CONCLUSUS, wherein are al things mysteriously and spiritually to be found, delicious in winter, then in Summer, in Autumne, then in the Spring ... where are al kinds of delights in great abundance... where are Arbours to shadow her from the heats of concupiscence; flowrie Beds to repose in, with heavenlie Contemplations; Mounts to ascend to, with the studie of Perfections.76

But the bond between pastoral nature and virginity is broader and more ancient than this; it goes back to priesthoods, vestals and fertility rituals. By the time of Ovid, the literary association of the pastoral Golden Age with the virgin goddess Astraea had become firmly established. In Vergil's apocalyptic fourth eclogue, Astraea ushers in the return of the Golden Age, and in Spenser's fourth eclogue, Astraea is identified with the Virgin Queen Elizabeth, "The queen of shepheardes all":

Ye shepherds daughters, that dwell on the greene, Hye you there apace: Let none come there but that Virgins bene, To adorne her grace And when you come, whereas shee is in place See that your rudenesse doe not you disgrace: Bind your fillets faste And gird in your waste, For more finesse, with a tawdrie lace.

(128-35)

The tight-laced virgin rose remains closed, self-protecting, immune from time, thereby retaining her integrity, her power over herself and her eternal youth. Artemis, the virgin sister and rival of Aphrodite, ranges the woodlands but also protects childbirth and childhood:

Whatever is coming to be and is not yet mature is under the care of this virgin Goddess. In Greece, young girls nine years of age were consecrated to her, and young men too, prayed for her protection. The very virginal intactness of the psyche protects what is immature and unripe,

52

Artemis takes care of the puer, for the young man is an image for the defenselessness and vulnerability of incipient developments in the psyche.78

Virginity is not exclusively a female attribute. For the young male, freedom from sexual desire itself appears like a pastoral condition, while its onset is experienced as a fall:

How happie were a harmless Shepherd's life

If he had never known what love did meane;

But now fond love in every place is rife

Staining the purest soule with spots uncleane79

Like Richard Barnefield's Shepherd, Spenser's Thomalin is a devotee of Artemis, out on a playful holiday hunt, delighting in the woods and the early springtime: "It was upon a holiday/When shepheardes groomes han leaue to playe,/l cast to go a shooting. Unknowingly, he comes upon Cupid disguised as a brilliant peacock, and suddenly the childishness of the shepherd boy's playing turns to earnest:

So long I shott, that al was spent:

Tho pumie stones I hastly hent,

And threwe: but nought availed:

He was so wimble and so wight,

From bough to bough he lepped light,

And oft the pumies latched.

Therewith affrayd I ran away:

But he that earst seemd but to playe,

A shaft in earnest snatched, And hit me running in the heele: For then I little smart did feele:

But soone it sore encreased. And now it ranckleth more and more, And inwardly it festreth sore Ne wote I how to cease it.

("March," 61 ff.)

The male adolescent experiences puberty as an encounter with an infantile energy in the guise of a splendid male sexuality. He

53

assumes that he can both conquer and play heedlessly with this force, but it quickly overwhelms him. Androgens spread through his body like poison. First they affect his physical and emotional equilibrium; then they begin to change his intellectual awareness and to pervert his social relationships.

Shakespeare presents the same idea of puberty as a fall in The Winter's Tale:

Hermione: you were pretty lordings then

Polixenes: We were, fair Queen,

Two lads that thought there was no more behind

But such a day to-morrow as to-day,

And to be boy eternal.

Her.: Was not my lord

The verier wag of the two?

Pol.: We were as twinn'd lambs that did frisk i'th' sun

And bleat the one at th' other. What we chang'd

Was innocence for innocence; we knew not

The doctine of ill-doing, (no) nor dream'd

That any did. Had we pursu'd that life,

And our weak spirits ne'er been higher rear'd

With stronger blood, we should have answer'd Heaven

Boldly, "not guilty"; the imposition clear'd

Hereditary ours.

Her.: By this we gather

You have tripp'd since.

Pol.: 0 my most sacred lady,

Temptations have since then been born to's; for

In those unfledg'd days was my wife a girl;

Your precious self had then not cross'd the eyes

Of my young play-fellow.

(I, ii, 63-68)

This anti-sexual attitude belongs to the rabbinical and patristic tradition of virulent mysogyny which identifies all women with Eve and sees them as the agency by which sin, guilt, mortality and time itself were introduced into a previously perfect and static world. Only in the happy prepubescent garden state was

54

true friendship possible; or, as Marvell would have it, only before the advent of women could boys maintain their intimate communion with mother nature.

In the series of "Mower" poems, Marvell chronicles the process of sexual maturation as the alienation from the green world of childhood innocence. Damon is first discovered in perfect sensual rapport with the rural environment:

I am Damon the Mower known

Through all the meadows I have mown.

On me the corn her dew distills

Before her darling daffodils:

And, if at noon my toil me heat,

The sun himself licks off my sweat;

While going home, the evening sweet

In cowslip-water bathes my feet.80

The first encounter with Juliana and with the pangs of heterosexual passion spoils the idyllic sensuousness of his joyful solitude by introducting desire, jealousy and despair:

How happy mought I still have mowed,

Had not Love here his thistles sowed!

But now I all the day complain,

Joining my labor to my pain...

(65-69)

Juliana not only pollutes the Mower's happiness by summoning desire in the first place, she then has the audacity not to respond to his advances: "How long wilt thou, fair Shepherdess/Esteem me and my presents less?/ ... thou ungrateful hast not sought/Nor what they are, nor who them brought." However, the fault ultimately resides not in the woman, but in the fated course of the Mower's own aging. Juliana is July, the hottest month of the dogstar's raging, the fever in the blood of life's summer season. Though he blames his hurt on her, Damon inflicts his wound and his fall upon himself:

55

The edged steel by careless chance

Did into his own ankle glance;

And there among the grass fell down,

By his own scythe, the mower mown.

(77-80)

Like Spenser's in "March," Marvell's satirical tone here underscores both comic and tragic implications of the theme: the adolescent male's helpless confusion in the face of his extreme and oscillating feelings toward women who appear threatening and desireable at the same time.

The erotic ideals of free love and chastity projected in pastoral provide escape from two evils attendant upon sexual pleasure: frustration and guilt. But there is another variety of the pastoral ideal of innocence which provides an alternative for the limitation and inadequacy of sexual intercourse itself. From the adult point of view-that is, one integrating the erotic into a larger texture of human relationships-the notion of an insufficiency in sexual intercourse itself may seem odd. But for the youth, whose bodily desire promises entry into a different world, the act of coitus often terminates in cosmic disappointment. As Renaissance poets never tire of warning:

Desire himself runs out of breath

And getting, cloth but gaine his death

Desire attained is not desire

But as the sinders of the fire.81

Some pastoralists think of "young love" as a release from this trap in the human condition. They envision practises which can combine the carnal joys of liberty with the protective shield of chastity, and which thereby can triumph over the defect in desire itself-its enslavement to time. Though this particular ideal finds explicit articulation less frequently than either free love or chastity, it is latent in much pastoral imagery, tone and allusion.

A suggestion of the contrast between innocent and fallen sexuality occurs in one of the Blake poems considered earlier,

56

"The Little Girl Lost." Suspending the standard interpretation of its theme as the conflict between youth and age, a second reading reveals that the children's free pleasure is spoiled not by the aged priests of civilization, but by the dynamic of desire itself. Before the girl encounters her father and her chilling guilt, she and her companion become "tired" of their daytime play in the grass and agree to a secret rendezvous under the cover of darkness. The father, in fact, tries to comfort rather than reprimand his daughter, for he recognizes the pain of her loss in the memory of his own. What "moral on the representation of Innocence" is Blake thus setting forth? I believe he is drawing the same distinction between the innocent love of sexual play and the guilty, time-bound quality of orgasmic sex that Ben Johnson elaborates in this unfamiliar version of the invitation to love:

Doing a filthy pleasure is and short

And done, we straight repent us of the sport.

Let us not then rush blindly on unto it

Like lustful beasts, that onely know to doe it

For lust will languish, and that heat decay.

But thus, thus, keeping endless Holy-day

Let us together closely lie and kisse,

There is no labour, nor no shame in this;

This hath pleas'd, cloth please, and long will please; never

Can this decay, but is beginning ever.82

In striking this contrast between the lustful sexuality

of "Doing" and the innocent pleasure of lying and

kissing, the narrator alludes to a number of pastoral

motifs. He renounces the "labour" that makes the act as

nasty, brutish and short as life in Hobbes' state of

nature. In its stead he advocates the endless holiday

otium of polymorphous petting. He emphasizes the

difference with a carefully orchestrated shift in tone

and rhythm. The anxious throbbing pulse of the first

part gives way to a leisurely meandering flow,

especially effective in the attenuated metrical pattern of

the penultimate line. And he expands the meaning of

the poem by suggesting that the

57

"filthy pleasure" of orgasm is subject to time and decay, while the chaste touching of foreplay can lead to the experience of eternity.

Andrew Marvell develops the same "metaphysical" conceit through another pastoral invitation. In "Young Love," he connects the prospect of unconsummated sexual pleasure to the ideals of childhood and the evasion of mutability:

Come little infant, love me now, Now then love me: time may take

While thine unsuspected years Thee before thy time away:

Clear thine aged father's brow Of this need we'll virtue make,

From cold jealousy and fears. And learn love before we may.

Pretty surely 'twere to see So we win or doubtful fate;

By young love old time beguiled: And, if good she to us meant,

While our sportings are as free We that good shall antedate;

As the nurse's with the child. Or, if ill, that ill prevent.

Common beauties stay fifteen; Thus as kingdoms frustrating

Such as yours should swifter move; Other titles to their crown,

Whose fair blossoms are too green In the cradle crown their king,

Yet for lust, but not for love. So all foreign claims to drown;

Love as much the snowy lamb So, to make all rivals vain,

Or the wanton kid does prize, Now I crown thee with my love:

As the lusty bull or ram, Crown me with thy love again,

For his morning sacrifice. And we both shall monarchs prove.

Critics have been reluctant to discuss this poem because of its ambiguous suggestions of radical sexual perversion.84 However, the children's play that the narrator proposes reflects a common Renaissance enjoyment of infantile sexuality:

The practise of playing with children's privy parts formed part of a

widespread tradition, which is still operative in Moslem circles. These

have remained aloof not only from scientific progress but also from the

great moral reformation at first Christian, later secular, which disci

plined 18th and 19th century society in England and France.85

58

The nurse's "sportings" with the child that Marvell alludes to are reported by Heroard, the court physician to Louis XIII of France, in a journal widely quoted by historians of childhood:

"He laughed uproariously when his nanny waggled his cock with her fingers," an amusing trick which the child soon copied. Calling a page, "he shouted, 'Hey there!' and pulled up his robe, showing him his cock."... The Marquise often put her hand under his coat; he got his nanny to lay him on her bed where she played with him, putting her hand under his coat . . . 86

Marvell is not as explicit as Heroard, but like Ben Jonson he states his preference by invidious comparisons with "Common" sexuality. Better than the lust of the bull or the ram, which engenders babies and diseases as well as "cold jealousies and fears," is the "wantonness" of kid or lamb. Such ideal love will antedate time by combining the erotic potentialities of young and old and by avoiding the temporal fall of orgasm.

The ambivalence about orgasm which fuels the longing for an innocent kind of sex permeates Renaissance psychology. Not only does "to die" have the secondary meaning of "come to orgasm" during the Elizabethan period, but popular physiology also held that each ejaculation was an "expense of spirit" that literally brought a man close to death during the experience, and shortened his life as well. Marvell alludes to the associations among orgasm, violent death and the constriction of time in the last section of "To His Coy Mistress," when he urges the lady to grow up and abandon her childish restraint:

Now let us sport us while we may;

And now, like am'rous birds of prey,

Rather at once our time devour,

Than languish in his slow-chapt power.

Let us roll all our strength, and all

Our sweetness, up into one ball:

And tear our pleasures with rough strife,

Thorough the iron gates of life.87

(38-44)

59

This call to experience functions as a 'Reply" to the pastoral Invitation of the poem's opening. There the speaker spins out a nostalgic vision of the ideal of polymorphous play:

Had we but world enough and time

This coyness, Lady, were no crime.

We would sit down, and think which way

To walk, and pass our long love's day.

Thou by the Indian Ganges side

Shoulds't rubies find: I by the tide

Of Humber would complain. I would

Love you ten years before the Flood

And you should, if you please, refuse

Till the Conversion of the Jews.

My vegetable love should grow

Vaster then Empires and more slow.

An hundred years should go to praise

Thine eyes, and on thy forehead gaze:

Two hundred to adore each breast:

But thirty thousand to the rest

An age at least to every part

And the last age should show your heart

For, Lady, you deserve this state

Nor would I love at lower rate.

(1-20)

The hypothetical "vegetable love" native to the green world conflates landscape with the erogenous zones of the beloved's body. By a kind of universal tumescence, both body and pleasure gradually enlarge to encompass all space and time. This is the final projection of the pleasure principle: the same infantile paradise of floating in the purely sensuous described by the Freudian psychologist as fundamental to all sexuality.

Several cults of carnal perfection have emphasized this ideal and have pursued the millenium in the form of an unending extension of sexual foreplay. Their practises are intended to provide escape from the temporal processes of individual aging and of human history and to be steps on the path back to the Garden of Eden. Known as "Karezza" in the love courts of Provence, Maithuna among adepts of Tantric Yoga, and Coitus

60

reservatus to the followers of J.H. Noyes in the 19th century utopian community at Oneida, all these disciplines have in common with pastoral's celebration of innocence a zeal to sublimate sex from its involvement with the cycle of copulation, birth and death. In doing so they neutralize its functions as the chief bonding force of worldly social relationships: marriage and the family.

The preference of premarital juvenile petting over adult consummated and procreative sex emerges clearly in one of the most popular of pastoral works, Longus' Daphnis and Chloe. Widely translated and imitated during the Renaissance, this late Greek romance chronicles the flowering of love between two foundling children of noble birth raised by Arcadian herdsmen. The story begins with descriptions of the infants suckling goats and sheep:

He saw the ewe behaving just like a human being-offering her teats to the baby so that it could drink all the milk it wanted, while the baby, which was not even crying, greedily applied first to one teat and then to another a mouth shining with cleanliness, for the ewe was in the habit of licking its face with her tongue when it had had enough.89

It ends with consummation of the wedding night:

Now, when night fell, all the guests escorted them to the bridal chamber, some playing Pan-pipes and some playing flutes, and some holding up great torches. When they were near the door, the peasants began to sing in harsh grating voices as if they were breaking the soil with hoes instead of singing a wedding song. But Daphnis and Chloe lay down naked together, and began to embrace and kiss one another; and for all the sleep they got that night they might as well have been owls ... then for the first time Chloe realized what had taken place on the edge of the wood had been nothing but childish play. (p. 121)

The beauty of this "childish play" is the subject of lengthy pictorial descriptions which fill the book:

So he went off with Chloe to the sanctuary of the Nymphs, where he gave her his shirt and knapsack to look after, while he stood in front of

61

the spring and started washing his hair and his whole body. His hair was black and thick, and his body was slightly sunburnt-it looked as though it was darkened by the shadow of his hair. It seemed to Chloe, as she watched him, that Daphnis was beautiful; and as he had never seemed beautiful to her before, she thought that this beauty must be the result of washing. Moreover, when she washed his back, she found that the flesh was soft and yielding; so she secretly touched her own body several times to see if it was any softer...

When they got to the pasture next day, Daphnis sat down under the usual oak and began to play his pipe. At the same time he kept an eye on the goats, which were lying down and apparently listening to the music. Chloe sat beside his and kept watch over her flock of sheep; but most of the time she was looking at Daphnis. While he was piping he