Fortunate Senex:

The Pastoral of Old Age

The other world of pastoral, for all its emphasis on spiritual and physical innocence, has never been the exclusive province of the young. Though one rarely encounters an Arcadian of middle age, the swain and the nymph have always shared their domain with a vocal populations of elders. Some are gentle seniors, like Vergil's Tityrus and Meliboeus, Sannazaro's Opico, Spenser's Melibee, and Lodge's Old Damon. Others, like Piers and Thenot in The Shepheardes Calender, Googe's Amyntas, Wordsworth's Michael and Frost's yankee farmers, are hardnosed, leatherskinned old countrymen. These characters are no trespassers in the rural landscape; their old age reflects their rugged settings and generates an essential bucolic vision of the good life.

Like youth, old age marks a pastoral stage of life because its world is situated on the peripheries of socially defined reality, remote from the center of court or city. In Victor Turner's term it is "liminal" to the worldly world possessed and created by those in their prime-mature adults who have completed the process of growing and who have not yet begun to shrink or walk on three legs.'

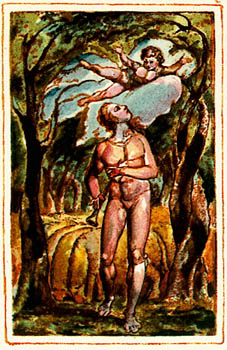

The shared exclusion of and by "the world" that attracts both young and old to the landscape of pastoral often brings them together into a tender relationship of mutual guardianship- a relationship that appears as a distinct bucolic motif from Vergil's Eclogues to Blakes Songs of Innocence. But just as often, when young and old meet in bucolic poetry, they find themselves in conflict rather than harmony. The debates of youth and age scattered throughout medieval and Renaissance eclogues provide an occasion for writers to articulate the attitudes and ideals of old age by contrast to those of youth and serve as exploratory essays on the meaning of life outside the limits of conventional society. But whether or not they appear in actual debates, all pastoral figures tend to feel emotions, espouse ideals, adopt styles and praise weather appropriate to one or the other-either youth or age.

Literary critics have been reluctant to recognize the pastoral of age.2 Such oversight may arise from the same general

88

societal preference that since the Renaissance has focussed more attention on youth than on age-witness the weight of psychological studies of early rather than late stages of human development. Neglect of the pastoral of age may also be due to the sentimental conception of the bucolic mode formulated by eighteenth-century theoreticians of pastoral like Rapin, Fontenelle and Thomas Purney.3 These writers insisted that the point of all pastoral was to project a vision of a simple, lazy and pleasurable life.

This theoretical approach is perpetuated in the work of many modern scholars as well. Thomas Rosenmeyer, for example, seeks to achieve thrift in the definition of the pastoral mode by banishing the old herdsman altogether. According to Rosenmeyer, the aged shepherd is never "central to pastoral," but belongs to the scheme of Georgic, a world "rustic, agrarian, Boeotian... [which] is what pastoral is not."4 The distinction upon which the expulsion is based on a distinction between idyllic Theocritean and realistic Hesiodic rusticity-is useful to delineate the antithetical primitivisms within the pastoral mode. But although they do signify distinct genres, "georgic" and "pastoral" cannot function as mutually exclusive categories. Looking back at his previous writings, Vergil himself conflated Eclogues and Georgics by referring to both at once as the rustic songs of aged Titryrus sung "with youthful daring beneath the spreading beech," and by grouping them as distinct from epic, which portrays active deeds of people in the middle of life.5 Youth, innocence and soft rural landscape may more readily suggest a utopian world, but old age, experience and the hard rustic setting also embody a vision of the good life, that is, "a pastoral."

As early as Vergil's first eclogue, the bucolic world is identified as the ideal home of the old age. "Fortunate senex," declares the unhappy old man who is forced to leave Arcadia to the one who is permitted to stay:

Lucky old man! And so the land will remain your land And for you it is enough...

89

Lucky old man! So here, among the streams you know,

Among the holy springs, you'll seek the shaded cool.

(1. 46-52)6

It is an old man, "reclining at ease beneath the cover of the shading beech," who first enjoys the "god-ordained" Mum or peaceful leisure that Hallett Smith has shown to be an essential pastoral ideal .7

In English Renaissance pastoral old men are usually the ones who extoll the virtues of the rural mean estate and reject the aspiring mind of the court and city:

Carelesse worldings, outrage quelleth

all the pride and pompe of Cittie:

But true peace with Sheepheards dwelleth,

(Sheepheards who delight in pittie.)

Perfect peace with Swaines abideth,

loue and faith is Sheepheards treasure.

What to other seemeth sorrie,

abiect state and humble biding:

Is our joy and Country glorie,

highest states have worse betiding.

Golden cups doo harbour poyson,

and the greatest pomps, dissembling:

Court of seasoned words hath foyson,

treason haunts in most assembling.8

These moral perceptions of Thomas Lodge's "Old Damon" justify his withdrawal from the court, but a force over which he has no control causes it. The rhythm of the life cycle demands his return to the natural setting from the artificial environment of the city. Gerontologists report that disengagement from the active and productive functions of a society defines the role of elder in almost every human culture. 9 Such disengagement and the corresponding shift of behavior from a mode of "active mastery" to one of "passive mastery" serves the welfare of old

90

people by removing them from stress, and serves the welfare of the whole system by liberating positions of authority for young adults to move into.

Youth and old age, grandson and grandfather, share the vantage of the peripheries, share distance from the center of social control and from the height of ambition. Traditional schemata of the Ages of Man picture old age as second childhood; the opening and closing acts of "this strange eventful history" of the life cycle form the lower steps of a pyramid, while adulthood stands at the peak. 10 The old man plays out his "golden years" in the green setting of the "golden age" of youth. Indeed, the pastoral of age often depicts the retirement of the soldier and the rustication of the courtier as a return to the haunts of his own childhood. Toward the end of his life, Don Quixote plans to unbuckle his sword and once again take up the oaten flute in the landscape from which he first set out; and Colin Clout "Comes Home Againe" after finding that ten years in the court have aged him prematurely. Shakespeare, as he approached the end of his active career in London and prepared to retire in rural Stratford, turned to pastoral convention in his last plays, focussing on the conflicts and harmony of youth and age in the bucolic retreats of Bohemia and Prospero's island."

As You Like It, the purest of Shakespeare's pastorals, stresses the partnership of old age and youth in the bucolic world, remote from the center. "Youth," "Young," "Old" and "Age" are among the words the dramatist uses most frequently throughout his career, but in no other play does any of them occur as often.12 The propelling force of the play's plot is the expulsion from the court of the young and the old by the aspiring minds of those who are middle-aged. Like most situations in the play, this expulsion occurs twice. Duke Frederick, the middle-aged brother, usurps the throne of his older brother, Duke Senior, and forces him into early retirement, along with a band of merry young retainers. Then Oliver, the fully adult older brother, deprives his younger sibling, Orlando, of education and patrimony and forces him

91

into the wilderness, accompanied by the ancient servant, Adam. Oliver's contemptuous epithets-"What, boy! ... Get you with him you old dog" (I,i, 49,75)-convey the adult attitude of the court toward both youth and old age. Upon reaching the forest of Arden, the young and the old find two different states of nature-one "soft," the other "hard"-but both discover in common the virtues of necessity. In the words of Le Beau, youth and age arrive in "a better world" than the one from which they have been ejected.

Orlando and Adam give up what little they are left with to help one another in time of need. Their common alienation from "new news at the new court" explains why pastoral so frequently depicts youth and age in the relationship of mutual guardianship. From Daphnis and Chloe to The Winter's Tale, aged peasants kindly rescue and raise foundlings abandoned by their royal parents, and are in turn protected and delighted by their charges. The guardianship motif, which also pervades folk-tale and fairy story, elevates the pastoral values of humility, naivete and tenderness, while denigrating the worldly virtues of fortune, wealth and power. In the Pastorella episode in Book VI of The Faerie Queene, the guardianship of the generations plays a minor but exemplary role. Spenser's silverhaired Melibee enters the scene to protect his foundling daughter from the evening chill:

Then came to them a good old aged syre,

Whose siluer lockes bedeckt his beard and hed,

With shepheards hooke in hand, and fit attyre,

That wild the darnzell rise; the day did now expyre....

She at his bidding meekely did arise,

And streight unto her little flocke did fare:

Then all the rest about her rose likewise,

And each of his sundrie sheepe with seuerall care

Gathered together, and them homeward bare.

(VI, ix, 13, 15)

92

In his version of the familiar pastoral dispraise of courtly life, Melibee equates the superior condition of his present rustication with his age and experience, but also with his childhood days, the days before he was pricked with the vanities of aspiration:

The time was once, in my first prime of yeares

When pride of youth forth pricked my desire,

That I disdain'd amongst mine equall peares

To follow sheepe, and shepheardes base attire:

For further fortune then I would enquire.

And leuing home, to roiall court I sought ...

With sight whereof soone cloyd, and long deluded

With idle hopes, which them doe entertaine,

After I had ten yeares my selfe excluded

From native, and spent my youth in vaine,

I gan my follies to my selfe to plaine,

And this sweet peace, hose lacke did then appeare.

Tho back returning to my sheepe again,

I from thence forth haue learn'd to loue more deare

This lowly quiet life, which I enherite here.

(Vl,ix,24-5)

But Spenser qualifies the cliche when he puts it in dramatic context. Melibee addresses his praise of the mean estate which harmonizes youth and age to the middle aged battle-weary knight, Sir Calidore. Calidore's longing is kindled by the old man's idea of the simple life of retirement, but it bubbles and boils as it mixes with the erotic pastoral of youth embodied in the shepherd's daughter:

Whylest thus he talkt, the knight with greedy eare

Hong still vpon his melting mouth attent;

Whose sensefull words empierst his hart so neare,

That he was rapt with double rauishment,

Both of his speach that wrought him great content,

And also of the obiect of his vew,

On which his hungry eye was alwayes bent;

That twixt his pleasing tongue, and her faire hew,

He lost himselfe, and like one halfe entraunced grew.

(VI, ix, 26)

The two-fold nostalgia for youth and for age immediately turns to disingenuousness in the mind of the sophisticated and aggressive courtier. Calidore attempts to manipulate the old man and seduce his daughter by reciting a rhetorical version of the primitivistic sentiments that are fully genuine only when uttered by Melibee. This is not deliberate deception, just a sample of the courtly manner by which a momentary sentimental flash issues in a fatuous pledge of lifelong commitment:

Yet to occasion meanes, to worke his mind,

And to insinuate his harts desire,

He thus replyde; Now surely syre, I find,

That all this worlds gay showes, which we admire

Be but vaine shadowes to this safe retyre

Of life, which here in lowlinesse ye lead...

Than even I...

Now loath great Lordship and ambition

And wish the heavens so much had graced mee,

As graunt me liue in like condition;

Or that my fortunes might transposed bee

From pitch of higher place, unto this low degree.

(VI, ix, 27-28)

The old man doesn't bite this lure any more than the offer of gold which follows. He knows that the pastoral cliches which are true for him are false when repeated by those who have not yet achieved the genuine disillusionment of age. In the first flush of enthusiasm Calidore experiences the pastoral world as "the happie life,/Which shepheards leade, without debate or bitter strife." (VI, ix, 18) But just as he himself envies the world which is supposedly free of envy, and just as the supposedly invulnerable condition of the mean estate is destroyed by the true meanness of the brigands, so the harmonious convergence

94

of the pastoral ideals of youth and age is unmasked in the framework of most pastoral poetry as the dialectical opposition of generational conflict.

The contrast between aged and youthful shepherds centers, predictably, on their differing perceptions of time. First of all, they regard history in opposite ways. The old herdsman thinks of the pristine prehistorical condition that all pastoral celebrates not as "the childhood of the race," but as the "good old days." For him, illud tempus becomes the Silver Age instead of the Age of Gold with its free love and eternal springtime; his version of cosmogony follows Hesiod and Ovid, who relate that the human race stagnated under the benign Saturnian reign. The Silver Age ushers in the order of time and the natural cycles of growth, maturation and decay, including the alternation of summer and winter.13 In the Judaeo-Christian tradition, the same change is marked by the fall, which brought about "the penalty of Adam/ The seasons' difference." (AYLI, 11, i, 5-6) While the pastoral of youth paints this fall into time and mutability as a disaster which destroyed the Mum of perfected human existence old shepherds think of it as a felix culpa into a salubrious educational regimen:

The father of mankind himself has willed

The path of husbandry should not be smooth

He first disturbed the fields with human skill

Sharpening the wits of mortal man with care

Unwilling that his realm should sleep in sloth...

So that experience by taking thought

Might gradually hammer out the arts...

(Georgics, 1, p. 17)

When the old herdsman invokes past greatness, it is a time of austerity rather than ease:

The time was once, and may againe retourne...

When shepherds had non inheritaunce

Ne of land nor fee in sufferaunce

But what might arise of the bare sheepe...

And little them served for their maintenaunce...

95

But tract of time and long prosperitee

Lulled the shepheards in such securitee. . .

Tho gain shepheards swains to look a loft

And leave to live hard and learne to ligge soft. . .

("Maye: 104-115)

To "moral on the time" is an appropriate occupation for the old shepherd. The temporal process in general and the winter wind in particular perform the invaluable service of teaching "who he is"-a phrase used both by Duke Senior and the newly converted Oliver to describe the instruction in selfknowledge offered by the forest. And old Opico repeats the lesson that his aged father taught him as a boy: though the world is sinking into worsening corruption, true virtue shines the brighter by contrast. Its very cost testifies to the value of the wisdom of experience:

And I. . .

Who am old indeed have bowed my shoulders

In purchasing wisdom, and even yet am not selling it.14

Old Thenot offers Cuddie a similar homily in Spenser's "February":

Who will not suffer the stormy time Where will he live till the lvsty prime? Selfe haue I worne out thrise threttie yeares, Some in much joy, many in many teares: Yet neuer complained of cold nor heate, Of sommers flame nor of Winteres threat: Ne ever was to Fortune foeman, But gently took that ungently came And ever my flocke was my chiefe care, Winter or Sommer they mought well fare.

(15-24)

Such teaching is antidote to the folly of youthful Epicurism-a source of Stoic fortitude.

96

Theriot's concern for the welfare of his flock and his sense of responsibility in the face of hardship exemplify another aspect of the pastoral of age. Otium, pleasure and play accompany the holiday pastoral of youth, but most old shepherds and farmers are more interested in an honest day's work. "My serious business gave way to their playing" says Vergil's old Meliboeus, referring to Corin and Thyrsis, "both in the flower of youth, both Arcadian, equal in song. "15 Pastoral's work ethos praises the down-to-earth labors that sustain the high and mighty of the world. This georgic aspect of the mode is what Empson designated as "proletarian literature." 16 Such literature describes the worker's tasks with an attention to detail that magnifies their dignity and charm. The pastoral of age also stresses that labor demands sweat-what Hesiod calls ponos or pain-and that painful effort has moral value. While youth invites the reader to "go with the flow" uniting nature and human nature, age teaches the discrepancy between desire and reality, and exhorts the reader to work against the entropic drive in the universe and himself:

. . . it is a law of fate That all things tend to slip back and grow worse As when a man, who hardly rows his skiff Against the current, if he once relax Is carried headlong down the stream again.

(Georgics, p. 19)

The universe ruled by this law requires not only sweat to resist the current, but also the canniness, the discrimination and the technique that only experience can provide. Vergil explains that though survival in a fallen nature demands unrelenting effort, the seasonal cycle also provides the clues and the tools that enable human beings to thrive-if they observe and learn. The paths of the constellations and the phases of the moon remind men of the correct days and times to sow, cultivate and reap, to plant vines, break oxen, warp looms.17 Time creates not only the necessity for work, but the possibility for success.

97

The stated purpose of Vergil's georgic is to draw attention to the appropriate connections of "Works and Days" and to disseminate the basic practical knowledge of a peasant culture. In preliterate societies such knowledge is lodged in the elders of the tribe and passed down from generation to generation. In postliterate agricultural and herding communities, the folk wisdom is often codified in farmers' almanacs, like the Kalendar of Shepherds that Spenser chose as one structural model of The Shepheardes Calender.18

The centrality of these georgic themes to the pastoral of age is brought to light in the tenth chapter of Sannazaro's Arcadia. Led by the ancient magus Enareto, old Opico conducts the uninitiated young shepherds to the sanctuary of Pan hidden in a cave. In front of the statue of the pastoral god stands an altar:

Down from either side of the ancient altar hung two long beechen scrolls, written over with rustic lettering; these were preserved by shepherds from one age to another in succession over many years and contained within them the antique laws and rules for the conduct of pastoral life, from which all that is done in the woods today had its first origin. On the one were recorded all the days of the year and the various changes of the seasons, and the inequalities of night and day, together with the observation of the hours (of no little utility to human beings), and unerring forecasts of stormy weather; ... and which days of the moon are favorable and which infelicitous for mankind's tasks; and what each man at every time ought to shun or pursue, in order not to transgress the manifest will of the gods... and how if one binds up the right testicle rams produce females and if the left males.

The wisdom of experience contains disparate precepts, but all in some way have to do with the proper use of time. The material question of the right time of day to cut the corn is related to the religious question of the appropriate time for prayer and sacrifice, to the moral question of when to trust and when to suspect, and to the political question of when to support and when to oppose the church or the government. In his "moral eclogues," dominated by aged shepherds, Spenser adheres to this tradition. In the envoi which sends his book from author to reader, he makes that adherence explicit:

98

"Loe I have made a Calender for everie yeere/ ... To teach the ruder shepherede how to feed his sheepe/And from the falsers fraud his folded flocke to keepe."20

As Spenser suggests, the work ethos of the pastoral of age demands a particular kind of intellectual and moral labor: the winnowing of grains of truth from the chaff of sentimental illusion. That winnowing gives sharp definition to the contrast between innocence and experience, and it gives shape to the most famous of all pastorals of age, "The Nymph's Reply to the Sheepheard":

If all the world and loue were young, And truth in euery Sheepheards tongue, These pretty pleasures might me moue, To hue with thee, and be thy loue.

Time driues the flocks from field to fold,

When Riuers rage, and Rocks grow cold,

And Philomell becommeth dombe,

The rest complaines of cares to come.21

Of course Ralegh's speaker is no old woman. But she repeatedly invokes the perspective of age while rejecting the childish appeal of the passionate shepherd's "Come live with me and be my love." Modulating from a caustic to a wistful tone, she lays bare the distortions of wishful thinking in the pastoral ideal of innocence by confronting that ideal with the practical wisdom of maturity. The age-linked nature of such ethical sifting was observed by lzaak Walton, who made the milkmaid's mother in The Compleat Angler append her recitation of both invitation and reply with this gloss:

I learned the first part in my golden age, when I was the age of my poor daughter; and the latter part, which indeed fits me best now but two or three years ago, when the cares of the world began to take hold of me. 22

The honest labor of differentiating sober verities from gay fantasy is the traditional function of moral satire, another mode

99

which plays an important role in the pastoral of age. The old shepherds in the eclogues of Barclay, Turberville and Googethe only pre-Spenserian English pastoralists-attack youthful recreation and erotic preoccupation in the accents of medieval moralists and old testament prophets:

And now to talke of spring time tales My heares to hoare do growe, Such tales as these I tolde in tyme, When youthfull yeares dyd flowe.

Now Loue therefore I will define

And what it is declare,

Which way poor souls it doth entrap

And how it them doth snare.23

According to old Amyntas in Googe's first eclogue, a clear understanding of what passion really is can alleviate youth's folly in love. He goes on to provide just that: a detailed physiological explanation of how kindled humors and poisoned blood break down the rational faculties.

In addition to pleasure, youth and love, the other chief target of the pastoral satire of age is the vice of those in high placesurban types in general and the hierarchy of court and church in particular. The winnowing of reality from illusion here involves unmasking the corruption beneath the veneer of glamour. Petrarch was the first to adapt the Old Testament figure of the ancient prophet crying out in the wilderness against the hypocrisy of the priests, and it continues to rail in the pastorals of Boccaccio, Sannazaro, Mantuan, Spenser, Milton and Blake .24 In "Lycidas," venerable St. Peter's invective interrupts the youthful narrator's elegaic mourning:

He shook his mitr'd locks, and stern bespake,

How well could I have spar'd for thee, young swain,

Anow of such as for their bellies' sake

Creep and intrude, and climb into the fold?

Of other care they little reck'ning make,

Then how to scramble at the shearers feast,

100

And shove away the worthy bidden guest; Blind mouthes: that scarce themselves know how to hold A sheep-hook, or have learn'd aught els the least That to the faithfull Herdsman's art belongs!

(108-121)25

And the limpid songs of Blake's child-inspired Piper in Innocence are succeeded by the strident homilies of the Ancient Bard of Experience, calling the lapsed soul to return and excoriating the abuses of king and clergy .26

Didactic satire traditionally demands the stile humile-the direct manner of speech and humble choice of words of the rustic. In contrast to the flowery, courtly language of the pastoral of youth, the aged pastor uses diction that is straightforward and often crude. This crabbed style has offended some readers of pastoral like Sidney and Dr. Johnson. Spenser's apologist, E.K., anticipated the criticism by pointing out the appropriateness of rough diction to old age and to the hard pastoral landscape:

... Tullie ... sayth that ofttimes an auncient worde maketh the style seem graue, and as it were reuerend: no otherwise then we honour and reuerence gray heares for a certein religious regard, which we haue of

old age as in most exquisite pictures they use to blaze and

portraict not onely the daintie lineaments of beauty but also rounde

about it to shadow the rude thickets and craggy clifts, that by the

basenesse of such parts, more excellency may accrew to the principall;

for oftimes we fynde ourselves, I know not how, singularly delighted

with the shewe of such naturall rudenesse, and take great pleasure in

that disorderly order.27

Though the harshness of this prophetic voice clashes with the mellifluous strains of the pastoral of youth, it is appropriate to the embattled seriousness of the pastoral of age. Many literary theorists have expressed aversion for the satiric aspect of pastoral and have also attempted to exclude it from their definitions of the mode. Poggioli, for instance asserts that "the bucolic ideal stands as the opposite pole from the Christian one," and Rosemeyer claims that "this [satiric] element is most

101

usefully employed to offset pastoral by way of contrast." 28 Once again, the polarity is real but the generic exclusion is misleading. The contrasting ideals and tonalities are best understood within the pastoral domain, where they correspond to the polarity of the seasons of the year and the seasons of human life. There pastoral satire finds its appropriate place in the natural scheme as what Northrop Frye calls "the mythos of winter."29

"Christian" and moralistic sentiments are almost invariably associated with pastors of advanced age, They are good rather than jolly shepherds, but they are shepherds nevertheless. Like youth's, their age's social position accounts largely for their expression of unconventional values. Like youth, they are outsiders, free from the pressures of sustaining families and institutions and from the entanglements of mutual support, threat and compromise that go with a place in society. Unlike youth, they have attained the wisdom of experience that enables them to transmit the non-secular values of that society. When Spenser draws on hard-working rustic heros of earlier British satire like Langland's Piers Plowman and Skelton's Colin Clout as tutelary presences of the Shepheardes Calender, he does not go outside the pastoral tradition but rather emphasizes the satiric strain of the pastoral of age.

That satiric and moral strain is also a response to the old person's treatment by a society that considers the aged as expendable. In AYLI, both old men, Corin and Adam, make mention of this abuse: "When service should in my old limbs lie lame/And unregarded age in corners thrown . . ." (11, iii, 41-2). Lawrence Stone reports that in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries the aged were victims of a number of social changes: "Old age had previously been seen as a time when weakening physical powers were compensated by the accumulation of wisdom and dignity; it now came to be seen as a period of decay of all faculties, as the body approached death .... Folly and miserliness were now regarded as the predominant character of the old people."30 As a protest against these abuses and on behalf of those "oppressed by two

102

weak evils: age and hunger," (11, vii, 133) biting moral satire forms an essential component of the pastoral of age. When Orlando sets down his "venerable burden"--the starving, exhausted old servant--Amiens sings a bitter version of the bucolic "song of the good life" which echoes the Senior Duke's famous praise of the sweetness of adversity:

Blow, blow thou winter wind

Thou art not so unkind

As man's ingratitude.

Thy tooth is not so keen,

Because thou are not seen

Although thy breath be rude.

Hey-ho, sing hey-ho, unto the green holly,

Most friendship is feigning, most loving mere folly;

Then hey-ho the holly

This life is most jolly.

(11, vii, 175)

Here, as in King Lear's ordeal on the heath, the metaphors and ideals of the pastoral of age are set forth in a tragic variation, whereby the wisdom of experience--"Ripeness is all"--can be won only at the cost of unbearable suffering.

This neglect and abuse of old age violates a number of traditional precepts. In rejecting its aged members, the society described by Stone denies not only its own past and future, but also its relation to any higher power. In almost all "primitive" cultures, the elderly are accorded positions of high respect because of their practical knowledge and their moral wisdom. But the central source of their veneration is old people's proximity to the realm of the sacred. Along with the poor and with children, those who have reached their later years supply a link to the Kingdom of Heaven. If infants trail clouds of glory from whence they came, "the elderly who are returning there already seem surrounded by the aura of its mystery."31

In traditional agricultural societies, special offices, like lighting the ritual fires of the winter solstice and Christmas, signal the nournenal quality of old age. They are also manifest in the

103

old person's cultivation of occult powers: "In the countryside during former times there was hardly an old person who wasn't a bit (or a great deal) of a sorcerer, breiche, as they say in old Provencal. Old people are divine." As they retire from the life of active involvement in the conflicts of history and of love, and eventually from the struggles of georgic pursuits and moral reformation, old people's abilities and concerns become more and more focussed on what David Guttman has designated "magical mastery": "...a relatively seamless fit exists in tradi

tional communities between particular social roles and psychic potentialities that are developmental in nature.... The religious role requires and gives definition to psychic potentials released by the older man's withdrawal from active tasks of parenthood and production. 1132

The learned tradition also identifies old age with the contemplative way of life. At the opening of The Republic, Socrates mentions his appreciation for age's wisdom, and Cephalus reports that "in proportion as bodily pleasures lose their savor, my appetite for the things of the mind grows keener."33 A closely parallel passage of Cicero's De Senectute reaffirms that philosophical proclivity, as do medieval pictorial schemata of the ages and the virtues.34 According to the symbolism of the vita triplex, the life of love and pleasure is appropriate to youth, the active life belongs to the middle years, whereas contemplation is the special province of old age. Thus, Basileus, the exiled king in Arcadia:

Old age is wise and full of constant truth

Old age well stayed from raunging humor lives: Old age hath knowne what ever was in youthe:

Old age o'ercome, the greater honor gives.35

In the pastoral setting, contemplative and magical mastery often involves an eclectic mixture of pagan and Christian elements. The topos of the old gnarled oak renders that chthonic sense of age's sacredness. In his tale of age and youth in "February," Thenot designates it as a symbol of "holy eld":

104

For it had been an ancient tree, Sacred with many a mysteree, And often crost with the priestes crewe, And often hallowed with holy water dewe.

(207-210)

The same oak magically appears in As You Like It to mark the power spot where Oliver is converted from a courtly hypocrite into a divine penitent:

He threw his eye aside

And mark what object did present itself

Under an oak, whose boughs were mossed with age

And high top bald with dry antiquity

A wretched ragged man, o'er grown with hair

Lay sleeping on his back...

(IV, iii 103-107)

At the end of the play Duke Frederick is also reported to have met "an old religious man" at "the skirts of the wild wood," and the recluse inexplicably awakened him from his erring ways. As a result, the Duke is said to have bequeathed his crown to his brother and to have remained permanently in the woods, taking up the calling of a holy hermit in a cave. And Enareto, the "holy shepherd" pagan priest of Sannazaro's Arcadia, is first discovered at the foot of a tree, his hair and beard long and "whiter than the flocks of Tarentina."36 In Drayton's "Seventh Eclog" Old Borrill sits musing in his sheepcoate "like dreaming Merlin in the drowsie Cell" and counts his beads. When Batte the shepherd boy tries to induce him to join in springtime frolics, Borrill offers a counter-invitation that states the old man's ideals of religious contemplation:

Batte, my coate from tempest standeth free,

when stately towers been often shakt with wind,

And wilt thou Batte, come and sit with me?

contented life here shalt thou onely finde,

Here mai'st thou caroll Hymnes, and sacred Psalmes,

And hery Pan, with orizons and almes.37

105

Renaissance pastoral often portrays religious devotion as age's replacement for the erotic devotion of youth, for instance in this lyric by George Peele:

His golden locks time hath to silver turned;

0 time too swift, 0 swiftness never ceasing!

His youth 'gainst time and age hath ever spurned,

But spurned in vain; youth waneth by increasing:

Beauty, strength, youth, are flowers but fading seen;

Duty, faith, love, are roots, and ever green.

His helmet now shall make a hive for bees;

And, lovers' sonnets turned to holy psalms,

A man-at-arms must now serve on his knees,

And feed on prayers, which are age his alms:

But though from court to cottage he depart,

His saint is sure of his unspotted heart.

And when he saddest sits in homely cell,

He'll teach his swains this carol for a song,

"Blest be the hearts that wish my sovereign well,

Curst be the souls that think her any wrong."

Goddess, allow this aged man his right,

To be your beadsman now that was your knight.38

Here the central pastoral ideals of contemplation, piety and the mean estate cluster around the reference point of old age. With a passing allusion to the change from gold to silver, the poem depicts the shepherd as an elder who has relinquished the vita activa of middle age proclaiming the primacy of the vita contemplativa over the vita amoris to a band of youthful swains sitting at his feet.

Competition between the claims of youthful love and aged contemplation generates the palinodal structure of much Renaissance poetry, whether or not it is explicitly pastoral in mode or debatelike in form. That contrast shapes paired and mutually contradictory collections of poems like Donne's Songs and Sonnets and his Holy Sonnets, or Herrick's Hesperides and his Noble Numbers. It also determines the design of Spenser's Fowre Hymnes:

106

Having in the greener times of my youth, composed these former two Hymnes in the praise of Loue and beautie, and finding that the same too much pleased those of like age and disposition . . . . I was moved ... to call in the same. But being unable so to doe ... I resolved ... by way of retractation to reforme them, making instead of those two Hymnes of earthly or naturall love and beautie, two others of heauenly and celestiall.39

And the reversal of outlook from youth to age that the self undergoes as it matures provides a frequent subject of lyric meditation:

I have lovde her all my youth

But now ould as you see

Love lykes not the falling fruite

From the withered tree.

Know that love is a careless chylld

And forgets promyse paste. . .

He is won with a world of despayre

And is lost with a toy...

Butt true loue is a durable fyre

In the mynde ever burnynge;

Neuer sicke, neuer ould, neuer dead,

From itself neuer turnynge.40

The dichotomy of youth and age is one of those conceptual polarities, like body and soul or nature and art, that Renaissance writers thought with as much as they thought about. It was linked with other polarities-like summer and winter, hot and cold, wet and dry, passion and reason-in astrological systems of correspondance that supplied a coherent, symmetrical picture of the cosmos. So familiar was that dichotomy as a way to organize ethical alternatives that the poet often mixed the extremes to suggest the unique, the paradoxical or the transcendent.

In As You Like It, Jaques tries to distinguish himself from the young men around him by adopting the old man's stance of satirical and contemplative wisdom. Despite others' recogni

107

tion of his pose's youthful callowness, at the end of the play, when they return to court, Jaques remains in the forest as an acolyte to one of its mysterious old hermits. And the speaker of Milton's "Il Penseroso" idealizes his aged future rather than his childish past by envisioning his attainment of "old experience" as another such sylvan sage:

And may at last my weary age

Find out the peaceful hermitage

The Hairy Gown and Mossy Cell

Where I may sit and rightly spell

Of every star that Heaven doth shew,

And every Herb that sips the dew;

Till old experience do attain

To something like prophetic strain

These pleasures melancholy give

And I with thee will choose to live.41

Echoing Ralegh's "Reply" to the Passionate Shepherd, the sober satisfactions of "I1 Penseroso" run counter to the youth

ful "vain deluding joys" praised in its companion poem, "L'Allegro." However, Milton locates the contemplative life not in a rough cave but in a place of comfortable repose, "a mossy cell." Here there is none of the harshness of landscapeor of native diction-that we expect of the pastoral of age. Instead of winter wind and rocky ground, there is an "Herb that sips the dew," and other delicate details that evoke the sensuous beauty of the locus amoenus. Milton's old man lives not in the woods but in a garden. Indeed, by the seventeenth century the word "hermitage" denoted an artificial grotto or deliberately fashioned ruin designed for sober meditation or relaxation. Found in most of the parks of great estates, it was as essential a feature as the erotic bower, and it was usually situated nearby.42

Milton's "I1 Penseroso" exemplifies what has been called "the pastoral of solitude," a strain of the bucolic tradition reflecting the cultural influence of neoplatonism.43 Much neoplatonic doctrine attempts to unify the divergent paths of

108

the vita amoris and the vita contemplativa by reconciling the corresponding conflict between young and old. Thus, at the climax of Castiglione's The Courtier, Cardinal Bembo discourses on the ladder of love as a means to transcend and thereby eliminate the antinomy of youth and age, pleasure and wisdom:

My Lordes, to shew that olde men may love not onely without slaunder, but otherwhile more happily than yong men I must be enforced to make a little discourse to declare what love is, and wherein consisteth the happiness that lovers may have.

And Pico Della Mirandola, in his "Oration on the Dignity of Man," refuses to accept the time-honored limitations of youth, claiming the sage's mantle for himself:

... and fathers, noone should wonder that in my early years, at a tender age at which it has been hardly permitted me (as some maintain) to read the meditations of others I should wish to bring forward a new philosophy.45

The neoplatonists symbolized their ideal of humanity in the ancient archetype of the puer senex, the youthful elder who combined vigor with sagacity.46 Sidney himself was remembered by Ralegh as one who fulfilled that ideal before his early death:

The fruits of age grew ripe in thy first prime,

Thy will thy words: thy words the seales of truth...

Such hope men had to lay the highest things

On thy wise youth, to be transported hence.47

The neoplatonic "landscape of the mind," like the concept of the puer senex, unifies the contrary pastoral ideals of innocence and experience. In Marvell's "The Garden," for example, youth and age come together in the setting of the sensual hermitage. The scene is described as "two paradises in one."48 It is both the green world of the body's infantile pleasure and the silver world of the soul's withdrawal into its own happiness. It preserves the past of prelapsarian enjoyment and

109

provides a foretaste of future flights. Here the speaker finds his own childhood condition of innocence, but he arrives late in life, after running his passion's heat and after ending a long career among the busy companies of men. With its harmony of pleasure and wisdom, love and contemplation, the neoplatonic pastoral of solitude mirrors the ideal of the mean estate embodied by Pastorella and other figures of mutual guardianship: a vision of the good life for youth and old age, coexisting "without debate or strife."

Perhaps the most memorable image of that concordia discors appears close to the source of both pastoral and neoplatortic traditions:

Here is the lofty, spreading plane tree and the agnus castus, high clustering with delightful shade. Now that it is in full bloom, the whole place will be wonderfully fragrant; and the stream that flows beneath the plane is delightfully cool to the feet. To judge from the figurines and images, this must be a spot sacred to Achelous and the Nymphs. And please note how welcome and sweet the fresh air is, resounding with the summer chirping of the cicada chorus. But the finest thing of all is the grass, thick enough on the gentle slope to rest one's head most comfortably.49

It is here, in this locus amoenus, this lovely spot outside the city walls, that we discover young Phaedrus talking love, rhetoric and philosophy with his master Socrates, the elderly sage.

NOTES

Victor Turner, Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969); also his "Variations on a Theme of Liminality," in Secular Ritual, ed. S. Moore and Barbara Meyerhoff (Amsterdam: 1977), 36-52.

2 In the rare instances that the old shepherd is mentioned, the significance of his age is largely overlooked. Kronenfeld, ("The Treatment of Pastoral Ideals. . ." p. 19, 145), mentions in passing the stereotype of "the wise old shepherd" as an example of the pastoral of contemplation, and she touches on the debate of youth and age in her discussion of the Colin-Silvius episode in AYLI, calling it "a minor convention of pastoral literature." (p. 177) In her excellent concluding chapter, "Nature and Art and the Two Landscapes of Pastoral," she once again mentions the opposition of the stages as a typical pastoral dichotomy congruent with soft and hard landscapes. Patrick Cullen (Spenser, Marvell & Renaissance Pastoral [Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 19701) discusses SC in terms of the Age-Youth debate, but sees that debate simply as a

110

corollary of his own idiosyncratic conception of the Arcadian-Mantuanesque dichotomy, not as an intrinsic pastoral convention. Renato Poggioli associates old age with what he calls "the pastoral of innocence"-i.e. the praise of humble felicity and the mean estate. But he supplies no explanation of why this bucolic ideal should be linked with elderly characters. He organizes his discussion of old shepherds around the archetypes of Baucis and Philemon, the aged domestic couple who appear in Ovid's Metamorphoses and Goethe's Faust. In my opinion, this "idyll of domestic happiness" is but one minor subdivision of the pastoral of age. (The Oaten Flute, p. 12). Later Poggioli says "adolescence and early adulthood are the only important pastoral ages" (p. 57).

3 See J. E. Congleton, Theories of Pastoral Poetry in England, 1684-1798 (Gainesville, Florida, 1952).

4 The Green Cabinet: Theocritus and the European Pastoral Lyric (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969), p. 58.

5 Vergil, The Georgics, trans. K. R. Mackenzie (London, Folio Society, 1969), p. 87. It may be objected that pastoral and georgic are distinct genres and traditions. However, their overlap has persistently confounded categorizers. See for example, John F. Lynen's book, The Pastoral Art of Robert Frost (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1960), Wordsworth's "Michael: A Pastoral," William Empson's discussion of "Proletarian Literature" as one "version of pastoral" and my arguments below. I believe the difficulty of separating georgic aspects of pastoral from pastoral aspects of georgic can be alleviated with the schema I propose.

6 Translated by William Berg, Early Vergil (London: The Athlone Press, 1974).

7 Hallett Smith, p. 2.

8 England's Helicon, ed. Hyder Edward Rollins(Cambridge: Harvard U. Press, 1935) 1, 24.

9 Wilbur H. Watson and Robert J. Jaxwell, Human Aging and Dying: A Study in Sociocultural Gerontology (New York: St Martin's Press, 1977), p. 31. This book and other gerontological studies cited later expand and revise the classic "disengagement theory" of aging.

10 Samuel C. Chew, This Strange Eventful History (New Haven and London, 1962), p. 162 Iconographical representations of the ages of man frequently include images of different animals for the different stages. Here again the life cycle subsumes human states into the order of nature.

11 In the case of Edmund Spenser, two recent critical works make mention of the poet and his persona's return to the pastoral world of youth in the retirement of his old age. See Isabel McCaffrey Spenser's Allegory: The Anatomy of Imagination (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976), pp. 366-70 and Richard Helgerson, "The New Poet Presents Himself: Spenser and the Idea of a Literary Career," PMLA 93 (1978) 895-6.

11 In AYLI, there are twenty-nine instances of the word "Young," twenty-nine instances of "Youth," fourteen instances of related words, like "Youthful." The nearest runner up is Twelfth Night, with twenty-two references to "youth." AYLI contains thirty-seven references to "old" and twenty references to "age." Marvin Spevak Harvard Concordance to Shakespeare (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1973).

13 A.O. Lovejoy and George Boas, Primitivism and Related Ideas in Antiquity, pp. 24-50.

14 Jacopo Sannazaro, Arcadia and Piscatorial Eclogues, Edited and translated by Ralph Nash (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1966), p. 68.

15 Vergil, Eclog 7, 1. 4, 17.

16 Some Versions of Pastoral, pp. 8 ff.

17 Georgics, p. 24.

"I The Kalendar of Shepherdes, vol. 111, ed. H. Oskar Sommer (London, 1892).

See also The Kalender of Sheephardes: A Facsimile Reproduction, Edited and with the introduction by S.K. Heninger Jr. (Scholars' Facsimiles and Reprints: Delmar, New York, 1979).

19 Arcadia, pp. 102-3.

20 The Minor Poems, vol. 1, p. 120. Though it is often referred to as courtly pastoral, and though its characters are thinly disguised stand-ins for members of the aristocracy and the royal family, even Marot's "Eglogue sur le Trespas de ma Dame Loyse de Savoye. . ." (1531) contains some homely advice of this sort, in the style of Poor Richard's Almanac. Here the aged shepherdess Louise (actually the Queen Mother) sits under an elm tree and addresses the daughters of neighboring shepherds:

Aulcunesfois Loyse s'advisot Les faire seoir toutes soubz ung grand Orme, Et elle estant au millieu leur disoit: Filles, il fault de d'ung poinct vous informe;

Ce West pas tout qu'avoir plaisante forme, Bordes, trouppeaux, riche Pere et puissant; 11 fault preveoir que Vice ne difforme Par long repos vostre aage florissant.

Oysivete n'allez point nourrissant, Car elle est pire entre jeunes Bergeres Qu' entre Brebis ce grand Loup ravissant Qu vient au soir tousjours en ces Fourgeres!

A travailler soyes docques legeres! Que Dieu pardoint ao bon homme Rober! Toujours disoit que chez les Mesnageres Oysivete ne trouvoit a loger.

For Louise, "Oysivete" or indolence-cognate with "otium," the pastoral ideal of leisure-represents a threat rather than a value. The elderly shepherdess warns her young charges that they should keep an eye to the future, that the wolf at the door cannot be kept away by riches or beauty or power, and that work, the virtue of the housewife, is the only way to prevent vice from deforming their tender ages. Oeuvres Lyriques, ed. C. A. Mayer (London, 1964), pp. 321-37. Translation: The Pastoral Elegy: An Anthology with Introduction, Commentary and Notes by Thomas Perrin Harrison, Jr., and English translation by Harry Joshua Leon (Austin, 1939), pp. 50-54.

Sometimes Louise would see fit to have them all sit under a great elm and being in their midst, she would say to them: "Daughters, I must inform you on one point. It is not everything to have a charming figure, lands, flocks, a father rich and powerful; you must take care lest through long idleness vice disfigure the bloom of your life. Do not encourage indolence, for this is worse among young shepherdesses than among the sheep is that big ravening wolf which always comes at evening to these thickets. So then be alert to work; may God pardon good Roger: he always said among good housewives indolence found no place."

112

21 The Poems of Sir Walter Ralegh, ed. Agnes Latham (Cambridge: Harvard U. Press, 1962) p. 17.

22 The Complete Angler or the Contemplative Man's Recreation of Izaak Walton and Charles Cotton, ed. James Russell Lowell (Boston: Little Brown, 1891), p. 88.

23 Barnabe Googe, Eglogs, Epytaphes, and Sonettes, ed. E. A. Arber (London, 1871) "Egloga prima," p. 32.

24 Frank Kermode, English Pastoral Poetry, From the Beginnings to Marvell (N.Y.: Barnes and Noble, 1952), p. 14.

25 John Milton, The Complete Poems and Major Prose, ed. Merritt Y. Hughes (N.Y.: The Odyssey Press, 1957), p. 122-3.

21 "Introduction," in Songs of Innocence and of Experience, ed. Goeffrey Keynes, plate 30.

27 Spenser, Minor Poems, p. 8. This contrast of diction reflects the distinction between what C.S. Lewis called the "aureate" or golden and the "drab" styles of sixteenth century poetry, a distinction that Yvor Winters reformulated as "Petrarchan" vs. "native." Winters asserted that the former style was artificial and decadent, a meaningless display of verbal pyrotechnics, whereas the latter style was honest and rational, the speech of a man speaking to men about a subject of real import. But in fact, most English-speaking poets use both styles interchangeably when playing different roles. In presenting serious ideas involving social and moral criticism, Wyatt, Surrey, Vaux, Ralegh, Donne and Greville often adopted the narrative pose of the old man, whether or not it corresponded to their actual age, and they moved into character by expressing themselves in the native plain style.

28 Poggioli, p. 1; Rosenmeyer, p. 26.

21 Anatomy of Criticism (Princeton: Princeton U. Press, 1957) Frye calls Satire one of "the mythical patterns of experience, the attempts to give form to the shifting ambiguities and complexities of unidealized existence." Frye's scheme of literary structures and genres analogous to the cycle of the seasons and to the contrary states of innocence and experience has influenced the formulation of my thesis about genre and life cycle. The parodic nature of the pastoral of age's "Reply" to the idealism of the pastoral of youth fits Frye's description: "As structure the central principle of ironic myth is best approached as a parody of romance: the application of romantic mythical frames to the more realistic content which fits them in unexpected ways. . ." (p. 233).

30 The Family, Sex and Marriage in England, 1500-1800 (London: 1977), p. 403.

31 Andre Varagnac: Civilization Traditionelle et Genres de Vie (Paris, 1948), p. 210 (author's translation).

12 "Alternatives to Disengagement: The Old Men of the Highland Druze," in Jaber Gubrium, Time, Roles and Self in Old Age (New York, 1976), p. 103.

33 The Republic of Plato, translated and with an introduction by F.M. Cornford (New York: Oxford University Press, 1945), p. 4 (1, 328); also see Adolf Dryer, Der Peripatos ueber das Greisenalter (Paderborn: 1939. N.Y. Johnson Reprint Corp. 1968); and Bessie Richardson, Old Age among the Ancient Greeks: The Greek Portrayal of Old Age in Literature, Art and Inscriptions (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1933).

34 Cicero's protagonist, the Stoic hero, Cato the Elder, defends the state of old age from attack by arguing that age's retirement from the active life means not disgrace and boredom, but freedom, time and energy for worthwhile private pursuits; that its decrease of animal spirits means not deprivation of enjoyment but release from desire, "the bait of ills"; that its closeness to death means not fear and trembling but the

113

broadening of perspective and the enrichment of contemplation. Cicero on the Art of Growing Old (De Senectute), trans. H. N. Couch, (Providence, R. I.: Brown University Press, 1959). In the course of this panegyric, Cicero reinforces the association between ideals of old age and rustic pursuits. In a long digression from the argument, his Cato enumerates the pleasures and satisfactions of farming which "approximate most closely the ideal life of the wise man." (xv, p. 51) Nature makes strong demands of self-discipline and effort but justly rewards those who have learned to benefit from experience. Contact with the soil, with the plants and with animals is also valuable for the old man, according to the speaker, because it provides intimate involvement with the workings of the life force in both its declining and regenerative aspects.

35 The Poems of Sir Phillip Sidney, ed. Wm. Ringler (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1962), p. 38.

- Arcadia, P. 95.

37 11, 19-24 in "The Seventh Eclog" in Idea: The Shepherd's Garland in The Works of Michael Drayton, ed. J. W. Hebel (Oxford: Oxford University Press: 1961) Vol. 5, p. 77.

38 Elizabethan Lyrics, ed. Norman Ault (New York: Wm. Sloan, 1949), p. 145.

39 Minor Poems, 1, 193.

41) The Poems of Sir Walter Ralegh, p. 23.

41 Complete Poems and Major Prose, p. 76 (11, 167-176)

42 See John Dixon Hunt, The Figure in the Landscape: Poetry, Painting and Gardening during the Eighteenth Century (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1976), pp. 1-9.

43 On neoplationism and pastoral, see Richard Cody, The Landscape of the Mind (Oxford, 1969) and The Life of Solitude by Francis Petrarch, Translated by Jacob Zeitlin (Urbana, 1924), p. 143, cited in Kronenfeld, p. 211.

44 Baldassare Castiglione, The Courtier, trans. Sir Thomas Hoby (1561) in Three Renaissance Classics, ed. Burton A. Milligan (New York: Scribner's, 1963), p. 592.

4-5

On the Dignity of Man, trans. Charles G. Wallis, ed. Paul J. W. Miller (New York: Library of Liberal Arts, 1965), p. 25.

46 E. R. Curtius, European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages, pp. 98-105. After tracing the appearance of the ideal of the puer senex from Vergil throughout medieval literature, Curtis concludes with a more general observation about this topos:

Digging somewhat more deeply, we find that in various religions saviors are characterized by the combination of childhood and age. The name Lao-tzu can be translated as "old child." . . From the nature worship of the pre-Islamic Arabs the fabulous Chydhyr passed into Isalm. 'Chydhyr is represented as a youth of blooming and imperishable beauty who combines the ornament of old age, a white beard, with his other charms.'

The coincidence of testimony of such various origins indicates that we have here an archetype, an image of the collective unconscious in the sense of C. G. Jung. (p. 101)

47 The Poems of Sir Walter Ralegh, p. 6

48 Marvell, ed. Joseph H. Summers (Dell: New York, 1961), p. 103, 11. p. 63-4.

49 Plato's Phaedrus, ed. W. C. Helmhold and W. G. Rabinowitz (New York: Liberal Arts Press, 1956), p. 7 (230).

114