From Playwright to Production:

the Process of Recreating Shakespeare

by

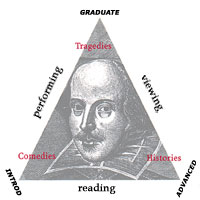

A full understanding of Shakespeare's plays is arrived at through

A full understanding of Shakespeare's plays is arrived at through

the process of imaginatively recreating them. Reading a play, or

watching a production, or being involved in a production, or reading what

someone else has to say is not enough fully grasp any given play. All of

these things must be done to achieve a deeper comprehension. On the

following pages I will try to organize my ten week Shakespearean

experience by drawing parallels between my own experience and the

experience of the rude mechanicals and royal audience of A Midsummer

Night's Dream.

Origin of a Shakespearean Production: The Bard Himself

Any representation of a Shakespearean work must necessarily begin

with Shakespeare himself. He is the creator and the genius behind the

dramatic works that hold a revered place in our literary and theatrical

culture. Part of what makes Shakespeare great is his consciousness of the

enduring role of the poet and a playwright. As a result, he wrote not

only for his own age but, in Ben Jonson's words, 'for all time.';

Shakespeare focuses not on what was popular and relevant in his

contemporary world, but on the themes that would be enduring beyond his

death.

Shakespeare's musings on the function of the poet and playwright

are included as themes of many of his plays. In A Midsummer Night's

Dream, Theseus speaks for Shakespeare at the beginning of Act Five:

The poet's eye, in a fine frenzy rolling,

Doth glance from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven;

And as imagination bodies forth

The forms of things unknown, the poet's pen

Turns them to shapes, and gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name. (Act V.i.12-17)

The poet is a visionary and his main tool is his imagination. Through his

imagination he looks at heaven and earth and sees what the average person

does not. The imagination gives 'bodies'; to and brings forth what cannot

be seen by the naked eye. The poet is given insight into a world beyond

what is seen every day of the surface of the world. He is like Bottom,

who when awakening after his adventures with Titania says:

I have had a most rare vision. I have had a dream, past

the wit of man to say what dream it was....The eye of man

hath not heard, the ear of man hath not seen, man's hand

is not able to taste, his tongue to conceive, nor his

heart to report, what my dream was. (Act IV.i.207-209,

214-21

The poet's vision is often above the normal senses of man to grasp what

it is through typical sense experience. Bottom unwittingly mixes the

sense organs with their senses, but he reflects the insufficiency of the

senses to grasp his vision. He cannot express, in the context of prose,

what his vision is. The only way to express such a vision is through art.

Art is the imaginative bridge that communicates a vision to an audience.

Bottom is a visionary, but not an artist. He identifies Peter Quince, the

only poet he knows, as the organ by which his vision can be conveyed to

the world.

Through poetry and the theatre, the poet and playwright express

what prose and logic cannot. Theseus says:

Lovers and madmen have such seething brains,

Such shaping fantasies, that apprehend

More than cool reason ever comprehends.

The lunatic, the lover and the poet

Are of imagination all compact. (Act V.i.4-8)

Through the medium of theatre, Shakespeare creates what reason cannot

understand. The 'the lunatic, the lover and the poet'; are all one type of

person. They see the world through the medium of the imagination. They

see what those, who see purely through reason, cannot.

In addition to the creation of settings and characters on the

stage, Shakespeare brings to life emotions and feelings within his

audience. He creates a world that speaks to his audience on the levels of

fantasy and emotion. Paulina of A Winter's Tale plays a similar role.

When Leontes has been blinded to the truth of the world by his faulty

reasoning, Paulina unlocks his emotions through a performance of her own,

in which she is both the playwright and the actor. Leontes, as a result

of the mini-drama orchestrated by Paulina, comes to see the love he first

felt for Hermione and shame for his treatment of her:

O, thus she stood,

Even with such life of majesty--warm life

and now it coldly stands--when I first wooed her.

I am ashamed. Does not the stone rebuke me

for being more stone than it? (Act V.iii.34-38)

Seeing the statue of Hermione does what all the reasoning of his advisors

could not do, it reawakens Leontes to the world of emotion which has long

been a 'stone'; to him. In the same way, Shakespeare forces an otherwise

passive audience to be a participant in his plays.

Reading the Play: Forming an Interpretation

For myself, reading plays the most important part of the

Shakespearean process. Reading gives me time to reflect on themes and

issues that Shakespeare incorporates into the play. It also gives me time

to dwell on the poetry and language that he uses. To watch a performance

of play by Shakespeare does not offer the time to reflect on individual

lines the same way that reading does. While watching, it is necessary

keep up with the plot at the rate of the performance if I have not read

the play beforehand. In this situation, I generally miss the thematic and

artistic development in the production.

Reading a play prior to a performance prepares me to take in

visual interpretations. When Puck observed the rude mechanicals

practicing their play in the woods he was able to make a judgment on

their performance based on his previous exposure to the story of Pyramus

and Thisby. He declares 'A strange Pyramus than e'er played here!'; when

he sees Bottom's portrayal of the part of Pyramus (Act III.i.89). In the

same way, my own reading helps me to make initial judgments of different

performances of the plays. Instead of having to take in a line and its

significance to the plot, themes, and on-stage representation, it is only

necessary for me to observe its representation, the other parts having

already been accomplished. Reading the play beforehand allows me to see

more clearly the director's interpretation of the play. Rather than

focusing on the words, I am able to observe the scenery and the various

character portrayals and how they differ from my own imaginative

recreation.

After reading King Lear, I watched three versions, the Laurence

Olivier version, the Peter Brook version, and the BBC version, paying

particular attention to Lear's performance in Act IV scene vi. I also

paid attention to my own response to the tragedy expressed in the scene.

In the Laurence Olivier version, almost the entire series of speeches

remained intact except for a few lines which were cut. Lear's descent

into insanity is recorded in this version. Because of his deep sorrow, he

is completely alienated from civilization, his mind wanders, and his

former majesty as a king has faded to a shadow. In response to Lear's

unlucky condition, I felt a pity, one of the key emotions that is

supposed to be evoked in a tragedy. In the Peter Brook version, whole

sections of Lear's speeches were left out. I noticed that these were the

sections that would be difficult not to interpret as insanity in Lear.

Brook obviously did not want a Lear who had lost control of his mind. He

instead presented a darker, more modern view of Lear's condition. The

Lear of Brook's version is in the depths of depression, not insanity. He

is locked up within his mind, rather than our of his mind. In response to

the portrayal of the individual alone in the harsh world, I felt fear,

the other key response to a tragedy. In response to the BBC version, I

felt only pain and disgust, the emotions felt when the attempt at tragic

effect fails. The director of this version tried to make a tragic scene

into a scene of comic relief by poking fun at Lear's insanity and

Gloucester's vulnerability. Based on my reading, I did not feel that this

interpretation was true to the passage or the play as a whole. Based on

my own readings, I could make the personal judgement that Olivier's

version is the truest to the scene, while the BBC version strayed the

furthest.

Shakespeare's writings are body of work that 'neither man nor

Muse can praise too much'; (Jonson). Consequently, there is a great and

extensive critical tradition concerning Shakespeare's work that is easily

accessible for reference. It has been beneficial for me to eavesdrop in

on this tradition while studying a particular play. Every article I have

read has illuminated the play I have been reading in some way or another.

Most of them offer insights into some historical background. Barber and

Montrose's essays on A Midsummer Night's Dream both provided me with a

historical backdrop to set the play in. Goldman's essay on Romeo and

Juliet drew my attention to how the language contributes to the play's

atmosphere. Seely's essay on The Winter's Tale draws a connection between

the play and issues that are important to today's world.

What the World Doesn't See: The Swanton Experience

There is one aspect of Shakespearean production that, unless an

individual is directly involved, is never seen. That is the time spent

learning parts, rehearsing, creating a unique interpretation, and making

a production that will be accessible to the target audience. This part of

the process is done away from the eyes of the world, usually behind

closed doors in a rehearsal room or, as in our case, at a location

secluded from the audience. This aspect of the process is done in secret

so that the final product may be revealed to the audience in its complete

form. Peter Quince and his cast of rude mechanicals take their rehearsals

out of town so their final product will not be found out.

But, masters, here are your parts; and I am to entreat

you, request you, and desire you, to con them by

tomorrow night; and meet me in the palace wood, a mile

without the town, by moonlight. There will we rehearse, for if we meet in the

city, we shall be dogged with company, and our devices known.

(Act I.ii.98-104)

Our cast did not meet in the enchanted woods of Athens, but we

did have the opportunity of being able to rehearse at Swanton Ranch among

the redwood groves and the 'murmuring surge.'; The chance to retreat from

the watchful eyes of the world gave us a chance to perfect our

performances. Performing among settings similar to those Shakespeare

described within his plays allowed us to live out the scenes in a ways

that are not possible on the stage. Working "on site" helped us to

sharpen our own visions and interpretations of what we read in the text.

The production of a play is a collaborative work. Each individual

involved comes with a vision to contribute to the production. Peter

Quince, the writer and director of 'The most lamentable comedy, and most

cruel death of Pyramus and Thisby,'; has his own vision of the play. After

meeting with the cast, a moon and a wall are added as character and a

disclaimer is written for the lion. Like Quince, as the director of the

King Lear scene, one of my roles was to come up with an interpretation

for the play. When I shared my interpretation with the cast, they in turn

added their own ideas and thoughts. Together we decided what details to

include and take out. Our final production was increasingly more fine

tuned as we neared the end of our filming time.

The Performance: Bringing an Interpretation to Life

In our performance, we tried to convey several interpretations.

First of all, we wanted to remain true to the theatrical effects

Shakespeare wrote into the Dover Cliffs scene of King Lear. We based this

interpretation on Harry Levin's essay, 'The Heights and the Depths: a

Scene from King Lear.'; In order to maintain Shakespeare's effects, we

needed to keep Edgar's plan a secret until he actually put it into effect

but at the same time, mislead the audience into thinking that he really

was planning to let Gloucester fall to his death. We tried to achieve

this by inserting a view of Dover Cliffs early in the cliffs, as if

setting the scene. We also did this by never showing what was in front of

Edgar and Gloucester during their final dialogue before the fall.

While trying to keep the actual setting a secret, we still wanted

to capture the scenes that Shakespeare painted so vividly through Edgar's

speech. We achieved this by conveying the scenes through Gloucester's

mind. The camera zoomed in on his eyes just as Edgar began describing the

scene. In this manner we were able to include the fisherman, birds, and

waves in our film without being untrue to the text. We originally wanted

to do most of Edgar and Gloucester's dialogue up to the fall within

Gloucester's mind, but we soon realized we were limited in the time,

technology, and knowledge required to achieve such an effect

successfully.

Finally, because we were filming only one scene, we wanted to

visualize the fact that none of the characters in the scene began their

story there. Act Four scene six is a transformative scene for all the

characters involved. We did not want out scene to seem independent of the

other events in the play that lead up to the scene. Our challenge was to

show through visual means, what we had to leave out. In our version, the

audience would not see the characters before or after the production, so

they could not see the changes that each character undergoes as a result

of the scene. We created a visual journey for the characters to bridge

part of this gap. Gloucester and Edgar begin the scene walking over a

variety of backdrops before they actually reach the cliffs. We do not

show Lear's journey with the same length, but he begins his scene coming

down a hill. He is descending from sanity to insanity. He is regressing

from a position of authority to a place where he is no longer in control.

For this scene, we learned how important details are in conveying a

message.

Being involved in a performance of a Shakespearean play has made

me aware of how closely the text directs a good performance and also of

how many different ways a performance can be directed. We filmed just on

version of the scene, but there were many different ways we could have

filmed it. The three versions of Romeo and Juliet that we saw this

quarter are a good example of how a text can inspire different

performances depending on the interpretation. The Zeffirelli production

emphasized the personal intensity and centralness of the main characters

by using close up shots of Romeo and Juliet. The Luhrmann version

presented a fast-paced and intense world through the use of dramatic

costuming and added plot elements, such as the car chase. The Cal Poly

production created a harsh world with a drab, steel set with rough edges

that was hard and unforgiving. These three performances represent just a

few of the ways that Romeo and Juliet can be recreated imaginatively.

Seeing a performance draws my attention to details that I had not

seen in the text. In Romeo and Juliet, the Prologue reminds the audience

that the actors will visually recreate what the words may not have been

heard by the audience. '[I]f you with patient ears attend,/ What here

shall miss, our toil shall strive to mend'; (Prologue 13-14). Any

performance is an imaginative recreation of what Shakespeare may have

seen in his mind when he wrote the play, what he may have seen if he had

written today, what the director sees, what the cast sees, or any

combination of the above.

The Viewing: How a Tragedy Can Become a Comedy

Often what an actor is trying to convey, is not what an audience

is seeing. In the Rude Mechanical's performance of 'Pyramus and Thisby,';

there is a gap between what the actors are trying to say and what their

audience understands. The actors are presenting a tragic story, but their

audience understands it as a comedy. The play that Bottom assures is 'a

very good piece work'; (Act I.ii.14) is later declared by Hippolyta to be

the 'silliest stuff I ever heard'; (Act V.i.211). Bottom expects to give a

moving performance '[t]hat will ask some tears in the true performing of

it: if I do it, let the audience look to their eyes. I will move storms,

I will condole in some measure'; (I.ii.26-29). He ends up moving the

audience to laughter, rather than tears.

Our acting experience seemed very similar to that of the rude

mechanicals. There was often comedy where comedy was not intended. During

our practices, we often laughed at the comic ways the tragic lines often

came out. It took practice to finally find a proper balance between

melodrama and monotone. Our inexperience with the technology was another

major source of comedy. We failed to fade out at one point and eliminate

a background comment. We also failed to check that our voice-overs and

music would be audible when the sound system was set up. The result was

comedy where tragedy and dramatic effect were intended. It was difficult

to resist being like Bottom and telling the audience what exactly was

happening and why they weren't seeing what they were supposed to.

Shakespeare knows that the audience needs to take the imaginative

leap between what they see and what they are meant to see during the

course of the performance. Theseus, the person every actor wants in his

or her audience, understands this concept. Theseus explains to Hippolyta

that:

Our sport shall be to take what they mistake:

And what poor duty cannot do, noble respect

Takes it in might, not merit.

Where I have come, great clerks have purposhd

To greet me with premeditated welcomes;

Where I have seen them shiver and look pale,

Make periods in the midst of sentences,

Throttle their practiced accent in their fears,

And, in conclusion, dumbly have broke off,

Not paying me a welcome. Trust me, sweet,

Out of this silence yet I picked a welcome;

And in the modesty of fearful duty

I read as much as from the rattling tongue

Of saucy and audacious eloquence.

Love, therefore, and tongue-tied simplicity

In least speak most, to my capacity. (Act.V.i.90-105)

A sympathetic member of an audience understands the difficulties faced by

the inexperienced actor. He fills the gaps left by the performance with

his imagination and tries to see, in his mind, what the actors and

directors saw in their minds. Of the actors he says, 'The best in this

kind are but shadows; and the worst are no worse, if imagination amend

them'; (Act V.i.212-213). Despite the errors, Theseus accepts the

performance graciously. The actors performance is merely an illusion of

the grandeur in their heads. Some crews are able to represent the image

better than others are. Theseus understands the vision behind both types

of actors and rewards effort rather than result.

Recreating Shakespeare is a visionary process that demands the

use of the whole imaginative vision of an individual. The individual must

be willing to look from many different viewpoints. Seeing the breadth and

depth of a work requires being able to look at it through the eyes of a

reader, critic, poet, actor, director, playwright, and audience member.

Anything else risks falling short of seeing the full extent of the vision

Shakespeare is giving to us.

| TOP |