from

Shakespearean Contingencies

by

Greg Choy

In his introduction to Shakespearean Negotiations, Greenblatt remarks, rather conclusively, that there is no escape from contingency. If I've learned anything from this Shakespeare seminar, it is that contingencies abound--between societies, cultures, eras, and literature, theatre, and film. I've learned also that contingency implies more than a touching upon or an illumination of the past in relation to the present, the dead in relation to the living. Contingencies create effects of and through time, bonds between the past and the present, causal relationships between the mainstream and the marginal.

As graduate students, most of us have come to know Shakespeare through classroom explications, scholarly articles, BBC videos, an occasional trip to see a live performance--exactly how this seminar started. However, by channeling our analyses through a New Historical perspective, we gained a familiarity with what, at times, can be a rather complicated "new school" of criticism. New Historicism became more accessible to me as we applied it to Shakespeare. I don't think I would have understood New Historical terms such as "subversion," "social energy," "exchange" had we not immersed ourselves in their application to Shakespeare.

But, suddenly, an era of literature came alive. Possible motives for these great works became an area of study worth consideration--in relation to what Greenblatt calls "the half-hidden cultural transactions through which great works of art are empowered." We were examining works from the aspects of those "half-hidden cultural transactions" upon which the mainstream was contingent not only for its dominance but for its very identity. The underlying lesson is a universal one: cultures are not isolated.

Limiting our study to three works worked to our advantage. It allowed for depth rather than breadth of study--and the class was, after all, a graduate seminar in Shakespeare, not an intro or survey course. I think we were all experienced enough coming into the course to be able to take subversive aspects of Henry V and decide whether or where they fit into the other History plays. We were all familiar enough with the Shakespeare canon to draw contingencies between the effect of ritual and belief in Macbeth and the ineffectiveness of them in King Lear. I think we learned much more about the whole of Shakespeare by delving as deeply as we could into three plays than by scratching the surface of a dozen (and then worrying about keeping to a particular schedule).

What added diversity to our depth study were the alternative productions. Again, to quote Greenblatt: "I want[ed] to know how cultural objects, expressions, and practices. . . acquired compelling force." Greenblatt's answer is through contingencies. Kurosawa saw them in Macbeth and created his own classic, incorporating aspects of the No drama, Buddhism, and the samurai. We recognize our presence in other times, other cultures, by observing how "cultural objects, expressions, and practices" familiar to us operate in different societies and different eras, we gain a deeper understanding of what makes us laugh, cry, go to war. As a composition instructor, I have often been tempted to spend an entire quarter on a single essay, having each student bring new insights, new approaches or perspectives to each revision. Too many essays in a quarter create the same skimming effect as reading too many works. As it is often enough to be able to read well rather than be well read, perhaps it is also enough of a beginning to think of a work: "Wow--I never thought of it that way," and create at least the possibility for exchange of imagination, creativity, and invention. The alternative productions offered insightful "re-visions" of Shakespeare's plays. They created meaning rather than simply reiterating it, they generated ideas and an exchange of interpretations which we could bring back to our reading of the original plays.

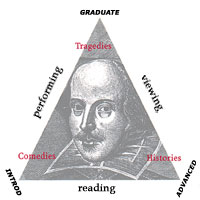

Of course, the best opportunity to take part in such an exchange occurred during our production of Twelfth Night. I am convinced that there is no better way to teach Shakespeare than through the combination of reading, witnessing performances, and staging performances. The first two methodologies I was already familiar with. The third, the acting, added what I can only describe as a magical quality to the study of Shakespeare. A transaction occurred between reading the lines aloud, memorizing them, blocking, and actually performing. A closeness to the character I portrayed developed that could not help but deepen my understanding of him and the entire play. I became aware of a personal propriety about the play that manifested itself in every gesture, every move on stage, in the very inflections of not only my words, but those of the other characters--an inexplicable, definite "feel" for the way things should be portrayed. The fullness of the characters we portrayed was contingent upon the extent to which we created and utilized that mysterious bond that I and certainly other members of the class came to realize must exist between actor and character--the freedom to invest that character with a sense of our "self" in conjunction with the restraints of the script.

I won't hesitate to say that this feeling was generated from a gradual familiarity with the characters of the play--through rehearsals and simply trying to perfect that smooth and natural flow of speech. However, contingent to that familiarity must have been the effect of what we had all previously learned about Shakespeare: new, revelatory aspects from the new Historicist approach, the diversity of character portrayals in the alternative productions, the implications of blocking and stage cues expounded by the Performance Theorists--I cannot help but think that what we learned about the plays in the classroom previous to our performance of Twelfth Night was somehow at the foundation of the success of that performance. Perhaps that "magical" quality can now more closely be described as a feeling of completeness or wholeness.

"That there is no direct, unmediated link between ourselves and Shakespeare's plays does not mean that there is no link at all. The 'life' that literary works seem to possess long after both the death of the author and the death of the culture for which the author write is the historical consequence, however, transformed and refashioned, of the social energy initially encoded in those works," writes Greenblatt. It's appropriate that after delving deeper into Shakespeare than I ever have before, I should return to these introductory statements by Greenblatt to clarify my experience. The fact is that much of Greenblatt eluded me at the beginning of the quarter. However, I can now say that after assuming a role, taking on a responsibility to accurately portray a Shakespearean character, to convey that character during a certain era, to speak the way that character spoke, to consider every word and how it can or should be uttered, how that character should walk, stand, gesture, cry, or fight, I think I have at least grasped Greenblatt's intent and context if not his definitions.

Carlos Fuentes posits that no culture retains its identity in isolation--that identity is attained in contact, contrast, and breakthrough. "Reading, writing, teaching, learning [acting!] are all activities aimed at introducing civilizations to each other." Finding contingencies between life and literature is part of what makes literature fun to read, worthy of study. The value of the three approaches we took to Shakespeare is not so much that they helped illuminate the contingencies, but that they helped make those contingencies come alive--ultimately through a union of his words and our voices and actions. Not to mimic Johnson's immortal words about Shakespeare, we were able to see Shakespeare evolve across a scale of history, as it were--through time, through cultures, not simply as a product of them. As the course progressed, I got the impression that we were not so much trying to speak with the dead as they were trying to speak to us through verbal, aural, and visual traces.

| TOP |