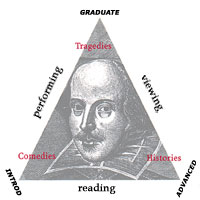

Scholar, Viewer, Performer:

Notes on Three-Dimensional Shakespeare

by

Patricia Estrada

Our 3-D approach to Shakespeare began with a scholarly roundtable of readings and research, focused around "archives" of research materials. By photocopying our independent research materials (or "archives"), and then distributing them to all class members a week before giving oral presentations on the direction of our research, each class member's path of inquiry was enriched by knowledgeable discussion of problems and discoveries. Research led to further research as we shared bibliographies. Comprehensive knowledge of our subject was possible if we did not work all alone. The process became addictive. (I am committed to teaching using this "archive" approach. I learned exponentially more than I would have in isolated research, and classroom rapport was enhanced.)

We generated mountains of materials and found it difficult to stop reading and researching and start writing. A few in the class were compelled, after their oral presentation, to request additional time to further clarify the direction of their research. We began to function as a collaborative Shakespeare think-tank and spun our ideas freely. We became completely absorbed in this process. Much of our research was historical, placing Shakespeare's plays in the context of his own era. But we also examined literary, social, religious and political correlations to our own time.

We then shifted from the role of literary critics and scholars and moved into the "audience" role, as viewers of performances. Perseverance furthers, and our one-day trip to San Francisco and back -- to see the live ACT performance of Twelfth Night -- cemented bonds amongst us as we edged closer to performing ourselves. The professional quality of the ACT performance, the large audience full of so many young people, and the silliness of the tropical stage setting continued the subliminal theme, which seemed to be that Shakespeare can and does take on myriad and most unusual forms.

Nothing can compare with live theater, but video productions of Shakespeare are easier to come by. With cassettes available from the library and from video rental stores, we could privately view and study performances. Videos are perfect for this, because they can be stopped at will. The viewer can watch any scene over and over and easily compare different versions. A comparative viewing of American, British and Japanese video productions of Macbeth demonstrated the different decisions directors inherently make about cuts and staging, depending on their interpretation of Shakespeare and their own artistic and cultural inclinations.

Then, finally, we moved out of the viewer role and began rehearsals for our performance. We began reading parts in small groups in classrooms, moved on to the larger rehearsal space available to us on campus in the agricultural barns (replete with tractor), and then began final rehearsals in the underground wine cellar (reminiscent of Fellini) where Twelfth Night would be performed.

Because I suffer from stage fright (and this never abated in two European tours performing folk music), I didn't want to act. But with "strong-arm" encouragement, I decided to participate and take a small role. Even though the part was miniscule, I immediately began to feel anxiety about the anxiety I might feel as a performer. An experienced actor in our group convinced me to "use" this feeling, not be used by it. This didn't prove easy, but I told myself to separate from the "self" and "reach" for controlled, contrived and then memorized movements and lines.

Classmates now suddenly became "cast members" and "characters" with new names. We reached for ways to understand, and then project, the most important essence of the words in the script. This "reach" drew us again and again back to the Bard, to his words in the text, to the stage directions. But it also drew us to each other. Together we would discuss what seemed to work or not work in scenes, what seemed to make sense according to our research. Sometimes the acting-out of a scene brought an "ah-ha" feeling of Shakespeare's meaning for the first time.

Cast members would stand backstage during rehearsals wondering together about what Shakespeare really meant about Puritans or Curates. This pondering was not primarily intellectual. It came from learning about performing together. A look, a voice tone, a movement... became the subtle, beautiful and irreplaceable moments of live performance. The whole cast felt let down the second night, because our energy was just not quite as high as the night before. Theater!

Shakespeare in this living theater realm -- no matter what the stage setting -- transports performers and audience into Shakespeare's own age through the vehicle of language itself. As performers we sought to use the vehicle of our voice, as well as the vehicle of body language, to connect with our audience. The living language of Shakespeare's English, staged so it seems to flow "naturally" between actors, and placed in the spatial context of the stage, aids comprehension and appreciation of Shakespeare for modern audiences, I feel sure.

The order of being scholar, viewer, then performer, was a useful one. Our inquiries into how to produce characters -- what will they look like, where will they stand, how will they enter and exit? -- were based on weeks of study and weeks of viewing performances. We could draw upon the many different versions of Shakespeare we had just seen. The whole cast shared this fund of common knowledge. We knew Shakespeare offered incredible lattitude to directors and performers.

From BBC to Playboy, we had viewed alternative productions of Shakespearean performances, and we were discerning viewers. From a black-and-white sparse medieval Japanese court (Kurosawa), to a saturated black-and-white expressionist Scotland (Welles), to a modern techni-color horror film (Polanski), we watched Macbeth stretched by directors to meet the performance needs of their "present." Literature in performance began to feel suspended in a slippery dimension of rubber time, where it was capable of taking on any form while remaining the same.

Such thoughts often kept me awake. Performing is a direct trip back to Shakespeare. Literature, history, religion, politics, arts, circus, spectacle -- all of this seemed to merge with the past. To experience this kind of collective joy and struggle in the unifying realm of literature is theater at its best!

At the personal level, my intellect was sharpened. This course moved fast and cut deep. Beyond my own search for meanings, for a connection with Henry V, Twelfth Night and Macbeth, was the group process as a whole. A great respect was tendered to this tentative collective groping. We let "our most weak gray-matters" wander about freely. And we took turns being guides. Each seminar participant invited the group to come along for an intellectual journey. With our archives as touchstones, we learned together and practised true intellectual discourse. We were supportive and constructively critical.

I was glad to learn from others, to see the fascinating processes of investigation and discovery unfold as class members moved ahead. (Normally, this independent part of learning is hidden away from professor and from classmates.) We rapped our own unique literary logic at the roundtable, and the group -- much like an editorial board -- threw out even more ideas and challenged weak areas. We divided up the topics and set out together, as a group of Shakespeare researchers. In doing so, the sense of competition was diminished and a more supportive group dynamic was forged.

The "audience" was never just the professor. From the beginning the aim was writing for publication. Also from the beginning, the goal was to share our research with all seminar members. For me, this was effective behavioral conditioning. Since I would be aiming for publication, I kicked into my editor/translator mode... "there can be no mistakes... every 'fact' must be double-checked, every source meticulously notated." Because I would share research with others, I had to prioritize source materials early (an extremely painful task) and decide which were worth photocopying. I read all the time, continuing my own research and reading others' archives. Not since I was a member of a Bay Area left-feminist publishing collective, have I experienced this kind of interactive and collaborative research effort.

My own research paper on Macbeth -- a rambling 22-page segue from the Celts in 1300 B.C. to the witches of the 1990s -- reflects my enormous, eclectic interest in mythic (magico-religious) images in the arts. A return to the study of myth (ala Joseph Campbell) is now taking place in such fields as anthropology, psychology, religion and literature. Why a renaissance of myth in the post-modern technical age? Who knows. But, as neo-conservative religion becomes a world political force, ancient belief systems and ancient myths are powerfully active in our own era.

The witches in Macbeth are creatures from the realm of myth and magic. But stemming from my research, I look at the witches in Macbeth and see images that represent 9 million European victims: martyrs burned as witches in a changing world order. I can only wonder why children are still taught to "honor" these victims by thinking of them as old evil hags who ride brooms once a year on Halloween! Their deaths are forgotten. We may knock on wood three times -- to prevent bad luck from striking -- and no longer know that we are using an ancient religious triadic form: the Druid's tree-god blessing. We so easily forget that we contain the past, but we must not forget! This course has reminded me of this. Shakespeare has come alive. I offer my two-clap Shinto bow to my English and European ancestors. I do not forget their lives and times.

| TOP |